Berggasse 19 is an impressive building of six storeys, located in Vienna’s 9th District. Built in 1889, it was the home and practice of Sigmund Freud for 47 years, until he and his family were forced to flee the Nazis in 1938. Eighty-five years too late for an appointment, I turned up for a look.

I was interested in visiting the Sigmund Freud Museum for a couple of reasons. First, regardless of the fact that nowadays some of his theories seem a little ‘out there’, Freud is a giant in the history of psychology, so I was interested to know a little more about him. Second, I had a couple of sessions of psychoanalysis a few years ago, which had left me a little confused about the nature of the therapy. So I was hoping a trip to the Museum would also give me a better understanding of ‘the talking cure’.

I entered the somewhat imposing front door of No. 19, and found myself in a modern space housing a ticket office, gift shop and cafe. After handing over my euros, I followed the staffer’s directions, and arrived in the stairwell of the building.

Imposing

I have to say, I did feel like I was walking in the footsteps of history as I climbed the stairs to the first floor.

Upon reaching the landing, I discovered that the door to the left lead to the Freuds’ residence, and the one to the right, Sigmund Freud’s office and consulting room.

To the left, or to the right?

Choosing to enter the residence first, I followed the instructions and rang the Freuds’ front doorbell. There was a buzz and a click, and I pushed open the door.

I found myself in the apartment’s ‘gentleman’s salon’, along with a goodly number of other visitors.

Cigar, anyone?

The Museum had not attempted to refurnish the Freud’s home (the family took their possessions to England when they fled), but instead presented personal items belonging to the family and copies of Professor Freud’s copious works.

Apparently Sigmund loved to get out and about for a look around, and travelled frequently. Amongst Freud’s holiday and study destinations were Greece, France, England, the USA and Italy. According to the museum, he visited the latter ‘nearly twenty times‘, and ‘His experiences on these travels are a lasting inspiration for the construction of his theories and his writings‘. It makes you wonder how different his theories and writings might have been if he visited Africa or Asia as well.

Freud enjoyed the creature comforts on his sojourns, choosing comfy hotels and enjoying fine food and wine.

He also took along this plush leather pillow in case he needed just a little extra comfort at any point

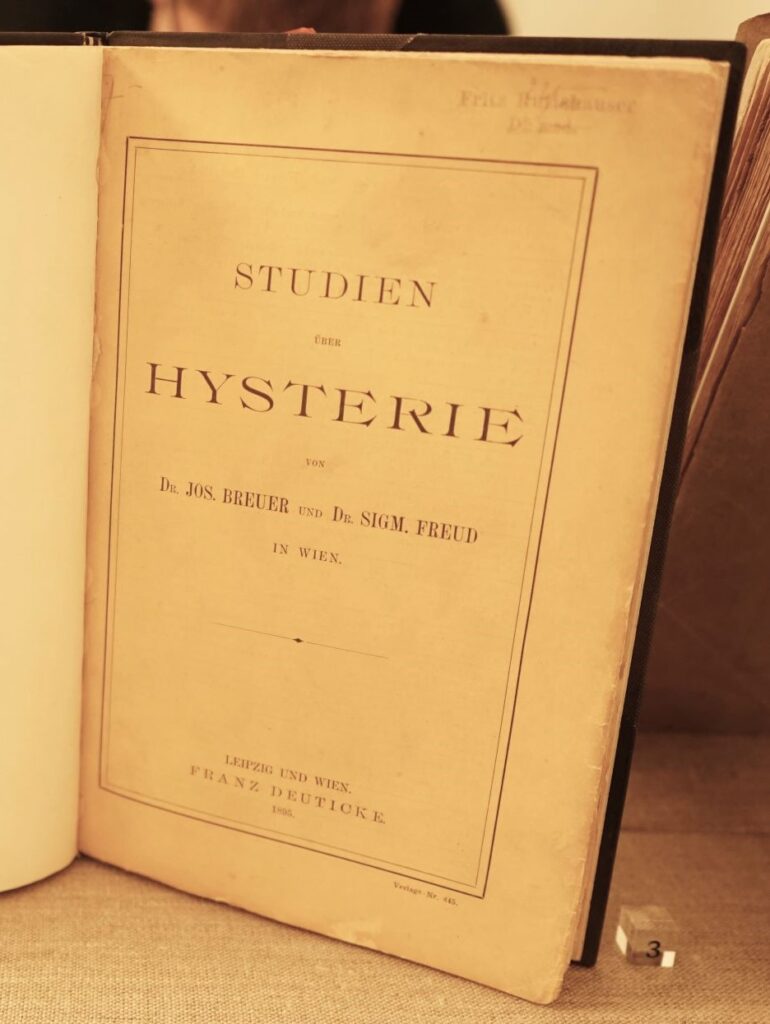

Professor Freud spent considerable time studying the phenomena of hysteria. In the 1800s, well-to-do, educated young ladies in Paris and Vienna were having hysterical episodes all over the place. Freud argued that the symptoms of hysteria stemmed from the psychological rather than physical, and were a result of childhood trauma.

Hysterical

This split from the previous theories of the cause of hysteria, including the ancient Greeks who believed a woman’s uterus (hystera in Greek, hence ‘hysteria’) could be on the move inside her body causing all sorts of trouble. Freud’s interest in hysteria made me wonder what he would have thought about the social contagions of the modern era.

One of the information panels within the Freud’s apartment made mention of Sigmund’s self-experimentation with cocaine. Presumably, if he was busted doing a line off his desk by his wife Martha, he could just pass if off as ‘research’. Interestingly, Freud believed that cocaine could be effective in easing the withdrawal symptoms suffered by morphine addicts. He tested this theory on a mate of his who was morphine addicted, and unfortunately soon had him hooked on coke too.

From the amount of work that Sigmund produced, and the number of sessions of analysis he would perform every week, one could reasonably conclude that it was all work and no play around the Freuds’ place. This photo proves otherwise however, showing Sigmund and Martha really whooping it up on their 25th wedding anniversary.

I spent some time moving from room to room in the residence, and learned a lot about Freud the man, his family and his areas of research. I had yet to find, however, a layman’s explanation of psychoanalysis. Still seeking answers, I left the apartment and crossed the landing, where I rang the bell and entered Sigmund Freud’s practice. If there was anywhere I was going to find out what psychoanalysis was, it would be there.

The doorway lead to the ‘practice wardrobe’, which the Museum explained still had its original furnishing.

This place sure would have seen a few coats

Turning right, I entered the waiting room, the only space that the Museum had reconstructed. Anna Freud (Sigmund and Martha’s youngest child who would go on to practice psychoanalysis herself) had provided some of the family’s furniture, making it possible to ‘bring at least one room back to its old form’. It certainly was like stepping into a bygone era, and I tried to imagine the many and varied citizens of Vienna (and beyond) who had sat in this room waiting for their appointment with Professor Freud.

From there I moved to the treatment room. It may be a hackneyed phrase, but ‘If these walls could talk‘ did spring to mind as I stood where Freud had conducted an untold number of consultations. Large format photographs showed what the room would have looked like back in the day.

Within the formerly plush room was the couch, the couch, which Freud preferred to call the ‘divan’ or ‘daybed’.

Upon this comfy spot the patients would recline, with Professor Freud sitting behind them, and be able to speak freely without having to make eye contact with the Doctor.

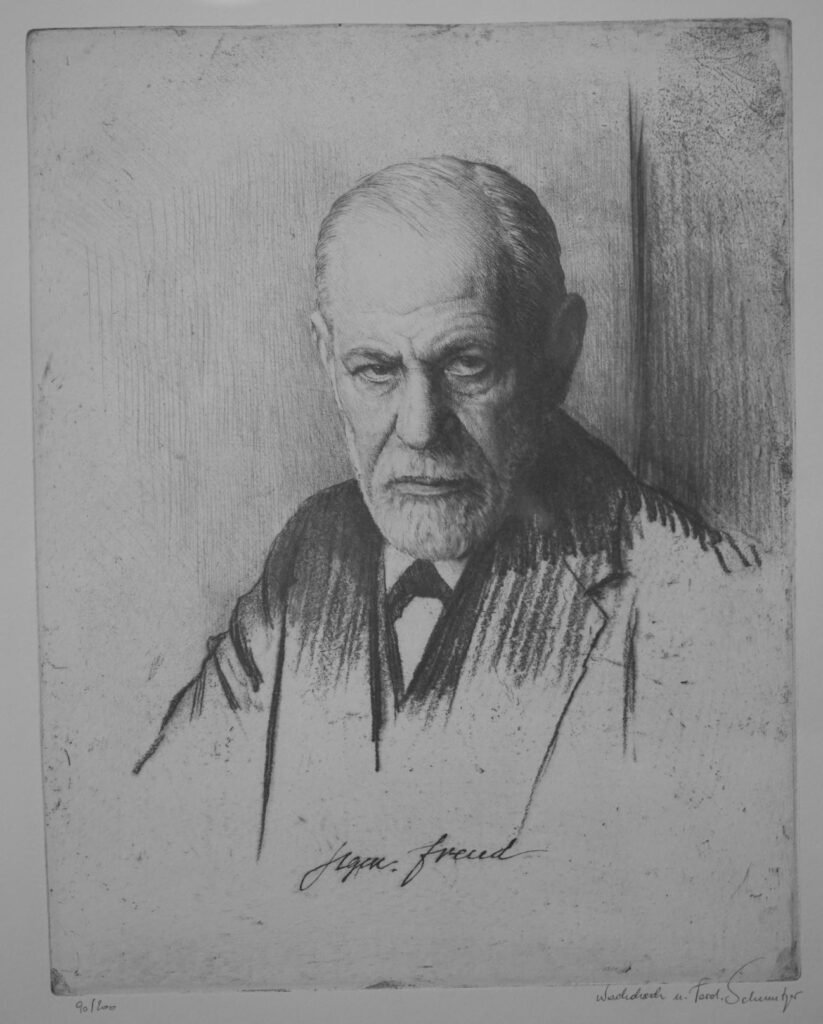

I expect this seating arrangement would be more conducive to revealing ones thoughts than having to sitting face to face with this bloke.

‘I want you to feel comfortable enough to tell me anything…’

Adjoining the treatment room was Freud’s study, where more photos showed a room well stocked with books and Sigmund’s collection of antiquities.

A portal to the past

It was in either the treatment room, or Freud’s study, that I found an information panel titled: ‘The Basic Principle of Analysis‘. Bingo.

Here’s what is said:

‘Freud’s psychoanalytic treatment is based on two principles: (1) in a relaxed reclining position, the patient utters everything that comes to his or her mind… (2) the analyst takes a seat at the side of the couch, or behind the narrator, and listens with ‘evenly-suspended attention’. Typical of the talking cure is its high frequency with several sessions a week. This facilitates the process of transference: unconscious desires and old relationship patterns are revived in the course of therapy and in the relationship with the analyst. Then as now, the goal of the talking cure is for the patient to become aware of such processes of transference – and thus allow for change – and to help the individual gain more autonomy, confidence, and empowerment and accept privation and sacrifice.‘

Well that answered a few questions I had after my two sessions of psychoanalysis a few years back, particularly the passive role of my therapist and being encouraged to speak about whatever came to mind.

Although I had assumed that my ramblings would eventually reveal patterns of thought to my therapist, I certainly wasn’t aware of the ‘transference’ concept.

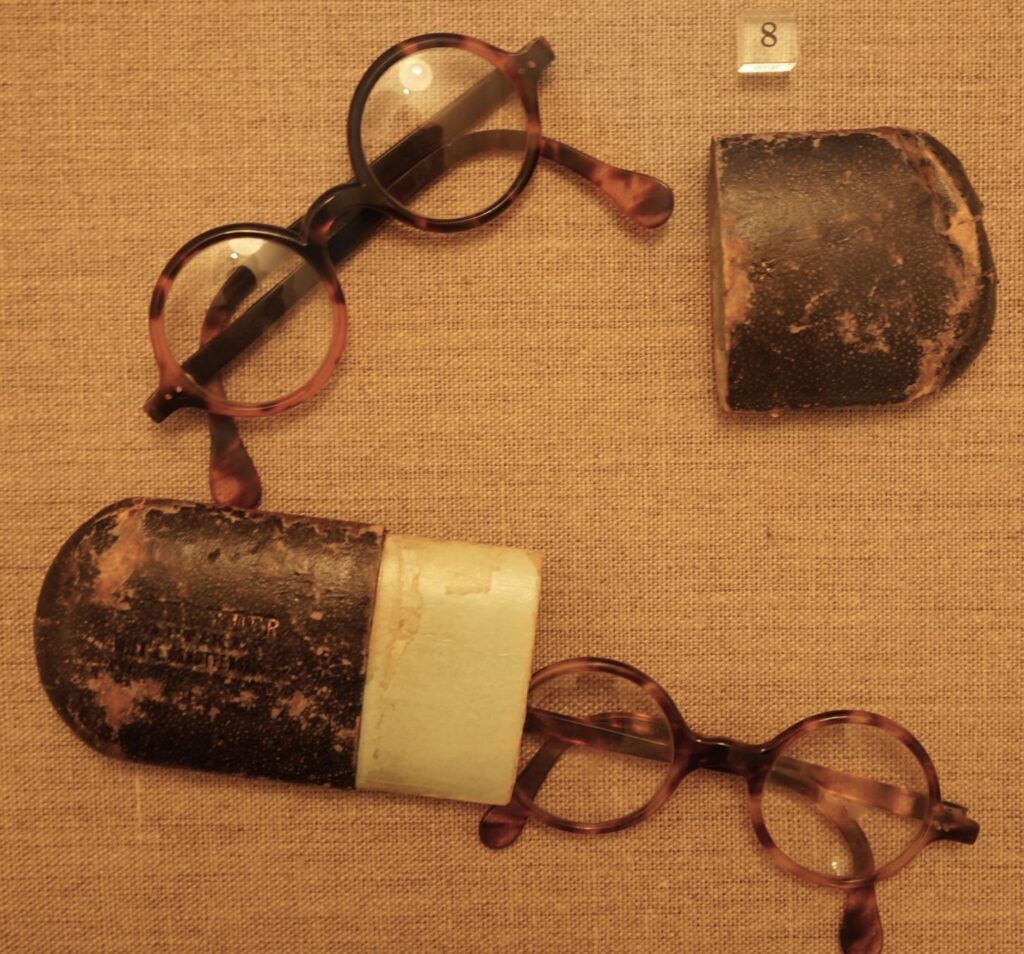

Freud always had a backup pair of specs ready to wear with his Harry Potter costume

I guess some might consider that ‘talking through your problems’ is a well-known and well-regarded way of helping to bring a little peace of mind. However the Museum pointed out that this was a reversal from the accepted doctor/patient dynamic back in Freud’s time. Presumably in those days, the doctor was the one that did the talking, told you what was wrong with you, and then prescribed some hideous procedure or medication to ‘fix’ it.

I had arrived at the Sigmund Freud Museum hoping to learn more about the man, and gain an insight into the process of psychoanalysis. After a few fascinating hours, I left feeling I had achieved both. Who knows if I will ever find myself in a psychoanalysis session again, but if I do, I’ll have a much better understanding of what to expect, and some knowledge of the man who created the ‘talking cure’.

Visit the Sigmund Freud Museum here

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like Visiting the Freud’s, Part I, The Bayeux Tapestry

Leave a Reply