With no aid distribution planned, I found myself with a wintry Sunday off in Zaporizhia. Naturally favouring an indoor activity, I did a little online research and discovered there was a car museum in town. Long suffering readers will know all too well my penchant for antique autos, and won’t be surprised that I was soon winding my way through the grey city streets to Zaporizhia’s industrial area. I expected to find a small place with a handful of soviet-era cars on display, but there was a whole lot more than that to the Phaeton Museum of Technology.

I must admit I was pleasantly surprised to find that the Museum was actually open. The war has forced many businesses and public facilities to close, and I have turned up to many places – advertised as open on the ‘net – only to find locked doors and security guards. However the Phaeton was open, providing a little escape for local families and me, looking for a weekend activity out of the weather. There were a couple of soviet era tanks on display in the car park, but these had been thoughtfully camouflaged. The air raid sirens started wailing so I hurried inside.

After buying my ticket I went into the first display hall, which was lined with cars from vintage to modern classics. A few groups of locals were wandering through the displays, pointing, chatting and laughing.

The first car which caught my eye was this Willys Overland Whippet. It’s not just because I reckon the Whippet is a great little unit, but rather that it had South Australian number plates. No, really.

Shaking my head slowly with mouth slightly agape, looking like the village idiot, I wondered, not unreasonably, how the bloody hell a vintage car from SA had ended up in a southern Ukrainian city. Small stickers on the dash commemorated the vehicle’s involvement in rallies in Whyalla and Port Augusta.

‘Yes mate, an SA plate…’

I have been away from Australia for nearly three years, and despite the fact that the display hall temperature was about 9 degrees, I felt a warm inner glow. I would definitely ask the staff about the car on my way out.

‘When a problem comes along, you must…’

In a confronting display of automotive style devolution (everyone who lived through the 80s is getting these gags), sitting opposite the neat elegance of the Whippet was this Arola 20. These were built in France between 1981 and 1983, and although there is definitely a point to developing microcars, do they always have to look quite so shithouse?

‘Nah mate don’t listen to ’em. It looks great…really…’

Talking of stye, the Cadillac El Dorado certainly can’t be described as ‘understated’. Considering the climate in Ukraine, you’d have to pick your day to go cruising with the top down.

A Ukrainian bloke standing beside me as I took in the gargantuan proportions of the El Dorado sparked up a conversation. When he paused I told him in Ukrainian that I was sorry but couldn’t understand what he was saying. Undaunted, he grabbed his phone and opened a translation app, and we had some laughs and a stilted ‘conversation’ about cars.

Beside the imposing El Dorado was this beautiful Lincoln H-Series. Leaving the car in (what I assume is) its original late-1940s paint job made for a great authentic display.

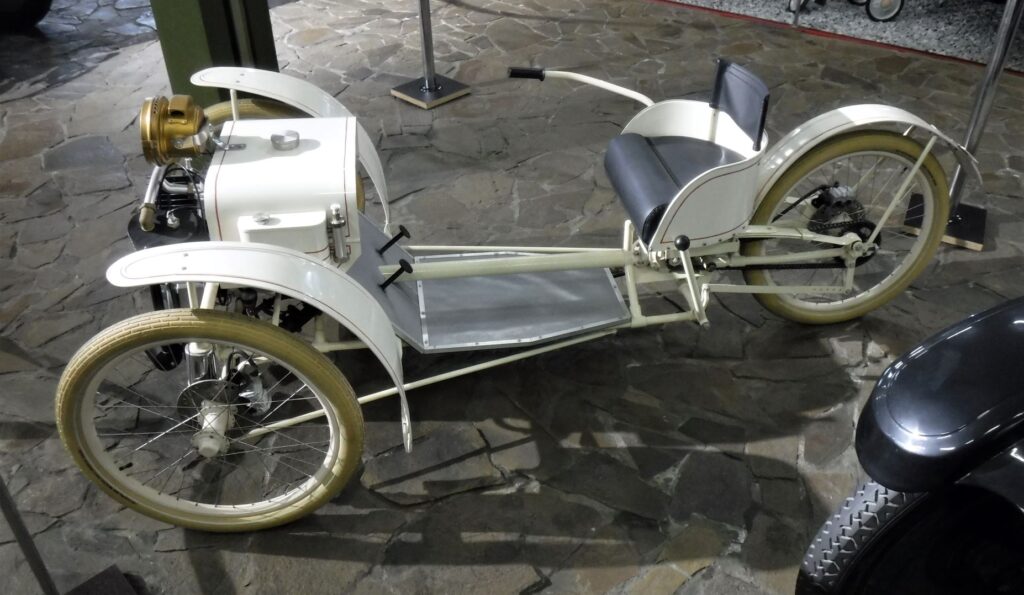

Moving through the first hall of the Museum, I came across this unusual vehicle with a sign reading ‘1909 Morgan Runabout’. Not at my sharpest, it took me longer than it should have to realise it’s a replica.

If you want to tear up the streets in your own Morgan Runabout, fitted with a clean, quiet and green electric engine (so arguably not strictly a replica as such, but it’s probably the closest thing to it you’ll find nowadays), you can order one from Ukraine! No, really! Well, probably not really at the moment, as the factory is in Mariupol and the Russians nearly destroyed the town before occupying it. Sadly the company hasn’t updated their social media page since before the war…

I dunno about you, but everytime I see a police car in a automobile museum, I always wonder if I would back myself to get away from it should the need arise. After all, there are some countries where getting pulled over by the police is not something to be unduly concerned about, and others where it is. Among the Phaeton Museum’s collection of GAZ-21 Volgas is this police car. At least I thought it was a police car, until I translated the the writing on the door, which seems to indicate it is a military vehicle.

Anyway, regardless of which branch of law enforcement the vehicle belongs to, the Museum information states the top speed of the 21 as 130km/h, and perhaps unsurprisingly I couldn’t find any acceleration information for the vehicle anywhere. Taking this into consideration, I decided that I would take my hypothetical chances at outrunning the Volga. Mind you, if I was in a Lada, I would have to quietly pull over and await my fate.

I was about to move on from the Volga when my new friend from the El Dorado appeared, this time with his English speaking wife on a video call. I had a short, pleasant if slightly odd conversation with her whilst my friend beamed at me.

But back to Soviet-era cars, the Phaeton Museum had, of course, heaps of them. I wandered into the second of the larger ground-floor display halls to have a look.

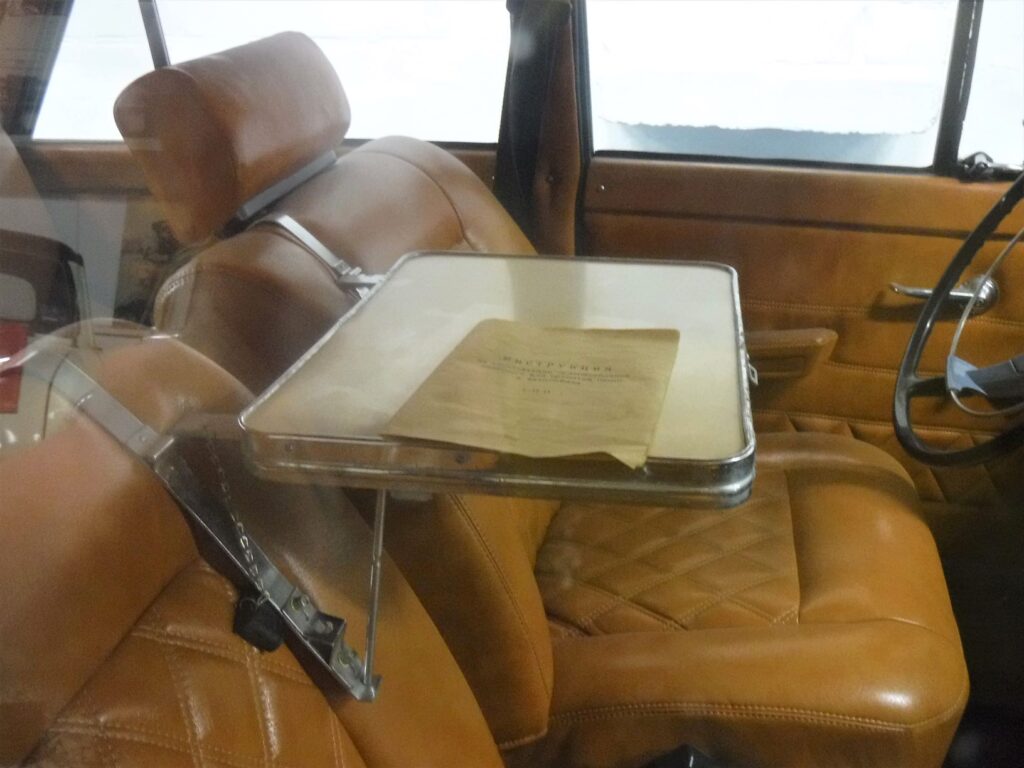

The line-up included this Moskvich 412, which might look a little ho-hum, but…

Yeah that’s a little ho-hum

…working on the go is a breeze with this neat optional front seat desk feature!

M never forgave Bond for leaving the file in the Soviet agent’s car

The Skoda Octavia Combi had a production run from 1961 to 1973, and despite its size, could really squeeze into those tight parks.

This Moskvitch roof-top camper would have been state of the art in its day. It possibly still is in some parts of the former USSR.

Low bridges on route to the camp site were a constant hazard

Amongst the hall’s ‘garagenalia’ was a display of car manufacturers logos from around the world. There amongst the brands was Australia’s Holden lion, now sadly just a museum piece since the marque was wound up in 2020.

‘Holden, Australia’s Own Car.’ Until it wasn’t anymore

After wandering through the Soviet car gallery I noticed a door off to one side. I wasn’t sure if it lead to more displays, or whether it was the entrance to the Museum’s offices.

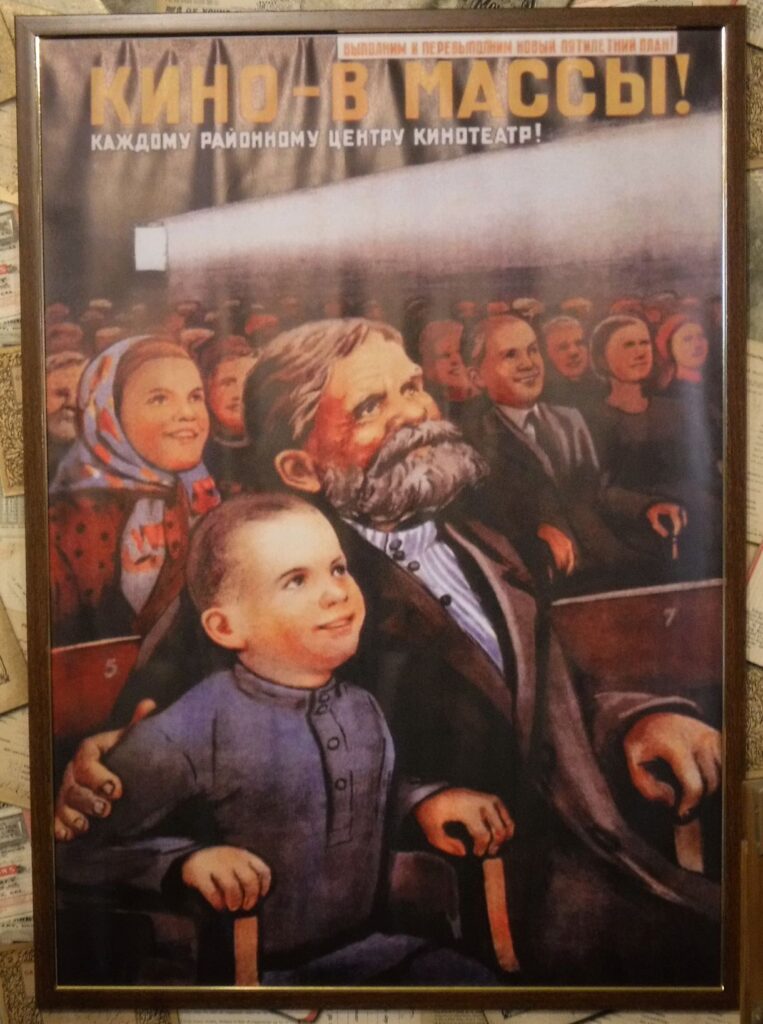

I opened it and had a peek, and found a room dedicated to old cameras, movie projectors, record players and sound equipment.

Think of the propaganda opportunities…

It was pretty cool to see all the old gear, and the film posters and movie star portraits from the past.

Young Sergei loved it when his dodgy uncle would sneak him in to the cinema to watch blue movies

After leaving the AV room, I headed towards the stairs that lead to the Museum’s upper hall. On the way I met my new friend again, who announced ‘selfie!’ before standing beside me and taking a few shots. We shook hands and he headed off beaming. Very friendly bloke. Loved to beam.

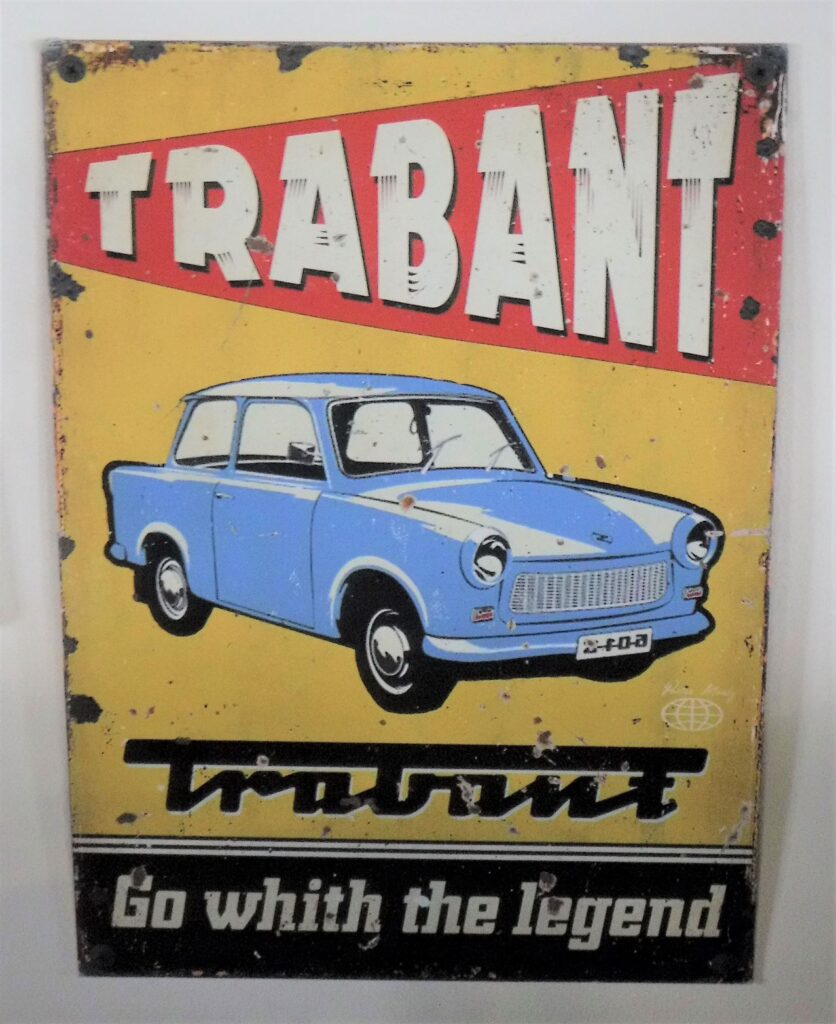

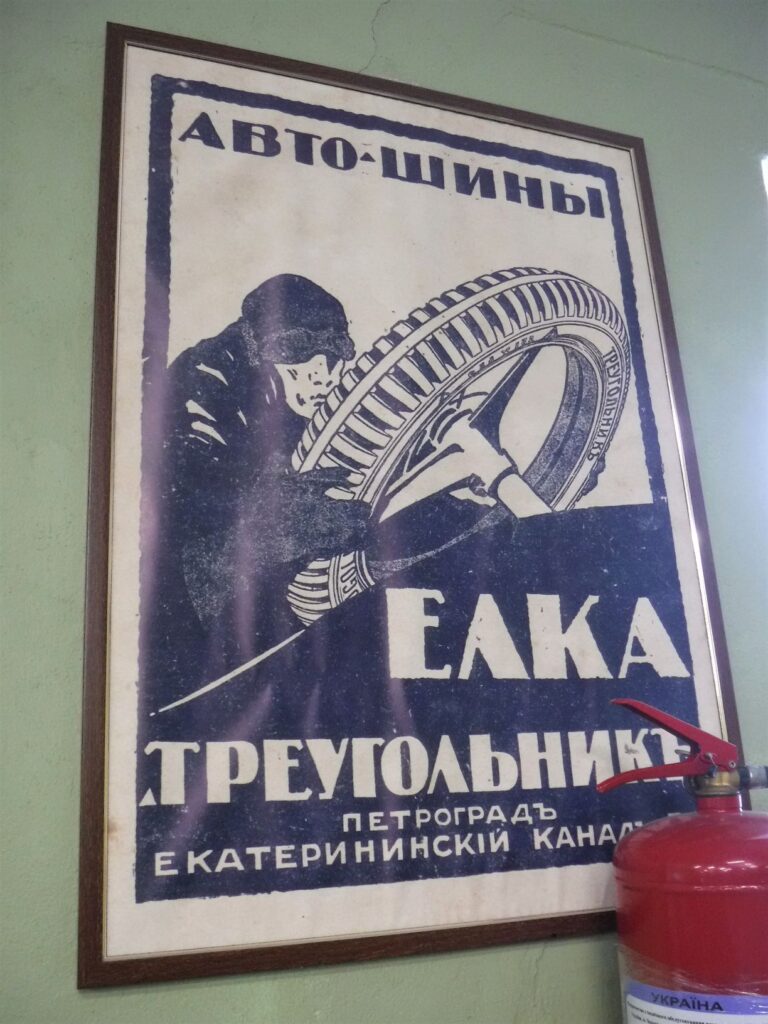

Climbing the stairs, I reached a mezzanine floor upon which a collection of scooters were displayed, along with more automobile memorabilia.

Like the mis-spelt ad, there were a few things not quite right with the Trabant

Early Soviet auto engineering had a few teething problems

Upstairs was a big collection of eastern European motorcycles, and more Soviet-era vehicles. Amongst these were a few racing cars, including this 1970 Moskvitch 412. I assume the vehicle is a replica of one used in the Daily Mirror World Cup Rally, as I expect a vehicle that actually competed in the 25,750km marathon would look a little more worse for wear.

I did a little research, and found that although Moskvich entered a factory team of five cars in the event, race number 98 was actually assigned to British-Leyland Cars’ works Triumph 2.5 Pi. Anyway, discrepancies aside, of the five Moskvich entrants, three finished the Rally with the highest placegetter coming home 12th. Considering that 96 cars entered the race and only 26 finished, I reckon that’s a pretty good result.

Soviet engineering is often criticised for looking a little agricultural, and this Estonia 21M open-wheeler (a model manufactured betweeen 1985 and 1992, according to Museum information) is a case in point. The Estonia was called the Estonia because it was built in Estonia, presumably by Estonians. Being unfamiliar with the name, at least with respect to cars, I checked out a webpage dedicated to the Estonia racers.

‘Anyone seen that steel plate I bought to make an engine cover for the tractor?’ ‘Nah mate can’t help ya’

After clicking the option to translate the text from Estonian, I discovered that 295 units of the Estonia 21 were built, and that is was one of a long line of race cars stretching back to 1957. I also found out that ‘Due to technical complexity, what had been achieved with the cars remained the production of new models and Estonia 22 and 23 were the only representatives to be delighted‘, although I’m not entirely sure what that means.

After several very enjoyable hours roaming the Museum, I headed back to the ticket desk to ask the staffer if she knew how the formerly South Aussie Whippet had ended up in Ukraine. She wasn’t sure, but mentioned that 80% of the cars at Phaeton were owned by one bloke (who presumably isn’t short of a few hryvnia). Perhaps he was perusing the classifieds section of Port Augusta’s The Transcontinental newspaper one Saturday afternoon, saw the Whippet listed, and snapped it up. The staff member was more interested in how the bloody hell I had ended up in Ukraine.

I had a great time at the Phaeton Museum of Technology. Although the war in no way effects me as acutely as it does the Ukrainians, it was nice to be a tourist again for an afternoon and forget about all the terrible things happening as a consequence of Russia’s invasion. I hope all the Ukrainian families I saw inside the Museum also enjoyed some respite from the harsh realities of being a nation at war.

Visit the Phaeton Museum of Technology here

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like Technology Museum Speyer, The Zastava 750 ‘Fica’

Leave a Reply