Leaving Ukraine didn’t quite go according to plan. After having inadvertently overstayed my visa by a day during my last stint, and having been reprimanded for it when leaving the country, I had been very careful not to repeat the mistake. I was therefore quite surprised to be hauled off the bus to explain why I had breached my visa by eight days.

It took 4.5 hours of miscommunication, confusion and fuck-ups to sort out the problem, which I still deny liability for, and during this time my bus left without me. I had grabbed my bag from the cargo hold just in case, so thankfully still had all my belongings. Instead of cruising across the Dnister River in the comfort of the bus, I ended up lugging my bags across the darkened bridge dividing Ukraine and Moldova at 3.30 in the morning.

I was certainly due for a change in fortune, and finally got a break when I found another bus on the Moldovan side. I located the driver and explained my predicament. Faced with a weary traveller down on his luck, stranded at an international border in the wee hours of the morning, he did what every decent, compassionate human being would do faced with the same situation: he ripped me off. Too tired to argue, I checked my dignity at the door, paid the asking price, and dropped into an empty seat.

Finally arriving in Moldova’s capital Chisinau (yeah I was calling it ‘Chizinow’ too, but it’s actually closer to ‘Kishinow’) about 0800, I walked the half hour to my accommodation and promptly fell asleep.

Next day I was ready to start exploring. Seeing as I knew very little about Moldova, and nothing about Chisinau, I figured a visit to the National Museum of the History of Moldova would be a good place to start. A short walk from my apartment and I arrived outside the impressive building.

Impressive

My Moldovan history lesson began before I even entered the building: outside in the grounds stood a collection of ancient funeral stelae.

The Museum information stated that these megaliths first ‘appeared at the end of the 4th – beginning of the 3rd millennia BC throughout the Northern Black Sea Region’.

‘Mate can I borrow your jumper?’

They are classified as ‘anthropomorphic’, and the artists certainly paid attention to detail, even carving this bloke a little arse.

Entering the building, I stumped up my lei for a ticket and entered the Museum’s first gallery: the mysteriously named ‘Red Room’.

‘And a pair of strides?’

Inside this gallery was the Museum’s oldest objects, providing a fascinating and sometimes frightening glimpse into what life was like in the ancient lands that would eventually become Moldova.

Many prehistoric animals had bloody big teeth, and when ancient people told their kids not to try and pat the cave bears, it was for good reason. This cave bear jawbone was mighty impressive.

Ouchy

In the same collection of, ahem, elephantine enamel was this mammoth tooth.

Museums generally frown upon visitors breaking into display cabinets to place a five cent piece or a lip balm next to an artefact to provide a sense of scale, so you’ll just have to trust me that it was mammoth.

Just the thing for a fibrous diet

It’s common to find old fish hooks in museums, but this is the first fishing lure I’ve seen on display. By the Middle Ages, Moldovans (who may actually have been known as Moldavians at this point, as from what I could figure out Moldova was actually called Moldavia in those days, but let’s just stick to Moldova and Moldovans for simplicity) were heading down the river on the weekend with these nifty lures in their tackle boxes.

Presumably the invention of Moldovan fishing lures tripped off a cascade of subsequent inventions, like the fishing rod, reel, camp chair, esky, stubby holder, and stubbies to put in them.*

Remember when you were a kid, and your parents gave you a moneybox in a vain attempt to stop you immediately blowing your pocket money on lollies? Well, if you were saving for a rainy day in 14th century Moldova, your piggy bank would be one of these neat little clay numbers.

Just the thing to save you losing your coins down the back of the couch

After leaving the Red Room I followed the arrows to the next gallery, which was chockers full of medieval goodies. Although a copy rather than an original ye olde set of chainmail, this suit of armour was still an impressive display. I can’t imagine it would have been comfortable to ride around in, as it must have caused some nasty chafing.

Long rides to the battlefield had the knights screaming for talcum

This striking portrait depicts Stefan cel Mare, aka Stephen the Great. He is a national hero in Moldova, having ruled from 1457 to 1504. That’s over 47 years, royal watchers! In modern day Chisinau, Stephen has his own boulevard, in which you can find a bronze statue of him. According to the Moldovan Government, Stephen is a legend for being a ‘good strategist and astute diplomat’, developing Moldovan culture by ‘founding a new architectural style’, building ‘an impressive number of churches and monasteries’, and fighting to ‘defend the integrity of the country’.

‘What did you say about my golden robes?’

After Stephen’s successes in protecting the borders of Moldova, things went a bit squiffy after his death. Like Eastern European history in general, what followed was an impossibly confusing period of wars, invasions, take-overs and general political machinations that I reckon you’d need to study for decades to get a handle on. Skipping forwards to World War II, the Soviet Union took over the territory that is now known as Moldova, and restructured everything to fit the communist model.

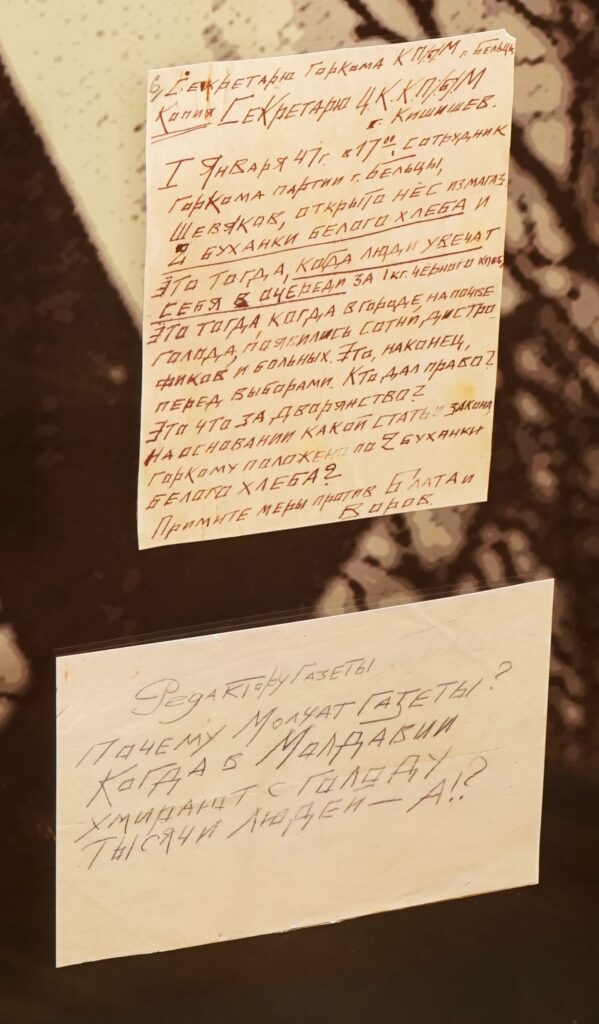

The Museum had a variety of displays covering the post-war history of the USSR, including these letters. Not everyone appreciated Stalin’s way of doing things, including one Nikolai Zalessky. He wrote to Stalin in 1947 to tell him so, and in reply received eight years of forced labour.

Stalin didn’t take criticism well

Whilst in this part of the Museum I was surprised to find an exhibit labelled ‘Torch of the XXII Olympic Games held in Moscow in 1980‘. A few years back I visited the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens, Greece, and saw what I thought was the Moscow Olympics torch in their museum.

Now, I guess there is likely to be more than one torch for each Games, just in case one breaks down and you can’t get the parts to fix it in time for the opening ceremony. And I imagine there is at least one Moscow Olympic torch in Moscow, since they were the host city and all. So that means there are at least three torches around claiming to the be the 1980 Olympic torch. It’s starting to sound a bit like religious relics.

This one here definitely looks like it has been lit at some stage, but was it actually at the Games, or just to spark up some Moldovan bloke’s Olympic supporters’ barbeque?

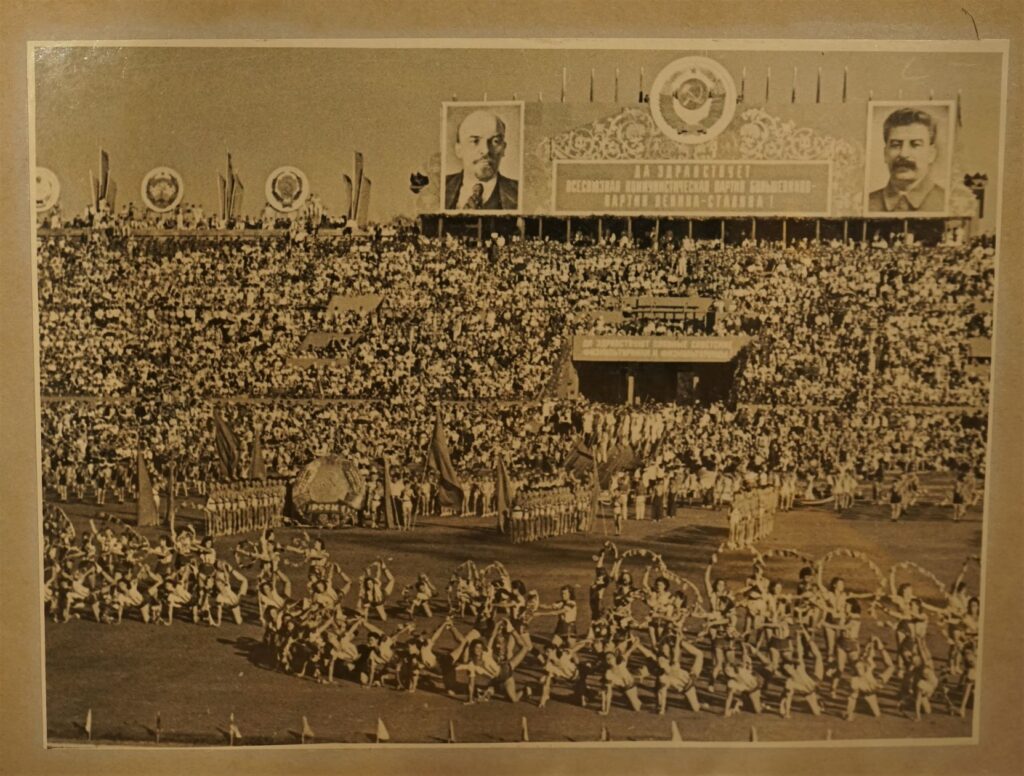

Talking of sports, there were a couple of photos on display from the opening of the Republican Stadium in Chisinau in 1952. Under the watchful eye of massive images of Stalin and Lenin, hundreds of athletes put on quite a show.

Strength sports were big in the former USSR, matched only in popularity by the contemporaneous State-sponsored doping of athletes.

Here are some solid female athletes performing the clean and jerk with grape-laden vine branches.

Much to the disappointment of Moldovan athletes, the grapevine clean and jerk was not included as a demonstration sport in the ’52 Helsinki games.

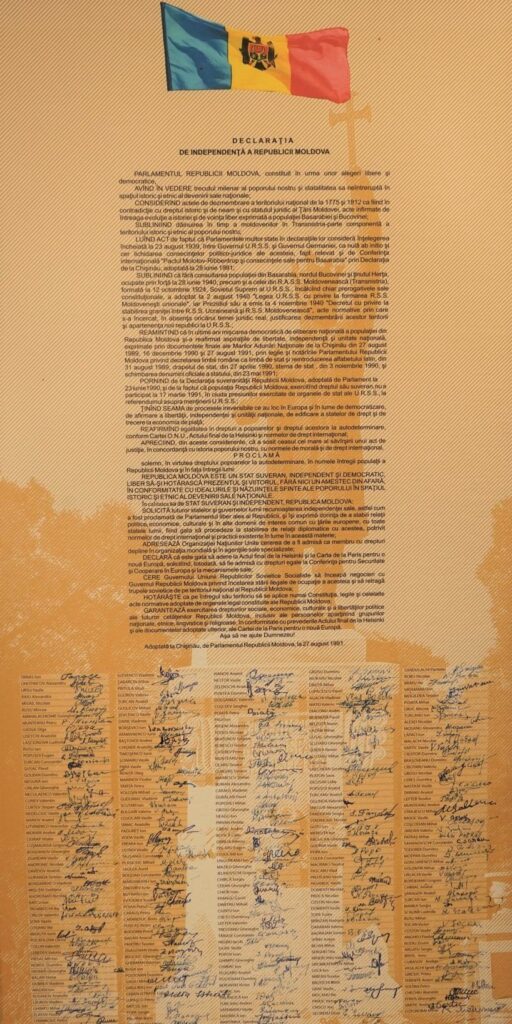

The collapse of the Soviet Union saw the emergence of the Independent Republic of Moldova, declared on the 27th August 1991. The Museum contained this framed copy of the declaration.

History museums in Europe generally leave me feeling both informed and confused, usually in equal amounts. This is because European history is very confusing, and many museums don’t feature much information in English (which is quite reasonable, unless of course they are an English speaking country, in which case it would just be odd).

Hurrah!

I definitely had these familiar feelings as I walked out of the National Museum, back past the anthropomorphic stele and his stone arse. However I certainly enjoyed my visit, and despite not being able to join all the dots, I had learnt a lot about the compact nation of Moldova.

*For our non-Australian readers, an esky is an insulated plastic box in which you put ice, followed by your perishable food and beers; a stubby holder is a neoprene sleeve with a base that you slide your stubby into to keep it cold; and a stubby is a 375ml bottle of beer.

Visit the National Museum of the History of Moldova here

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy Acropolis Museum, Museo Picasso Malaga

Leave a Reply