Ancient Athens, Part I

Athens is a modern, vibrant city of over three million people. Clustered between the mountains and the shores of the Aegean, it is one of the most densely populated cities in Europe. It is also the ancient heart of the Greek Empire, the birthplace of democracy, and a bloody interesting place to spend a couple of weeks.

I grew up in Melbourne, which, at least when I was a kid, had the second biggest Greek population of any city outside Athens. I followed (and still do) the Carlton Football Club, born in the inner city where may Greek and Italian families settled after World War II. The Blues’ playing list included many players having Greek heritage (Alex Marcou, Spiro Kourkoumelis, Evangelis ‘Ange’ Christou and Anthony Koutafides to name a few). I reckon Athens’ winter weather is pretty similar to Melbourne’s too, and perhaps all this explains why Athens felt quite familiar to me as I began to explore the city.

Dominating the Athens skyline is the Acropolis, the heart of ancient Greece, sitting atop a mesa overlooking the modern city. It’s a very handy landmark for the newcomer, greatly assisting the navigation of Athens’ maze of winding streets and alleys. In order to protect the extraordinary collection of ancient artefacts found at the Acropolis, the aptly named Acropolis Museum was built. I figured it would be a pretty good place to start my journey into Greece’s long history.

The Museum is a modern, state of the art facility built over the remains of a neighbourhood dating back to 4000 years BC. You can view the archaeological site from the entrance, and from inside through the many glass panels in the Museum’s floor. You may ask why the Museum was built right over the top of an ancient structure, until you realise that pretty much the entire city is built upon the remains of something ancient, which was in turn built upon something even ancient-er.

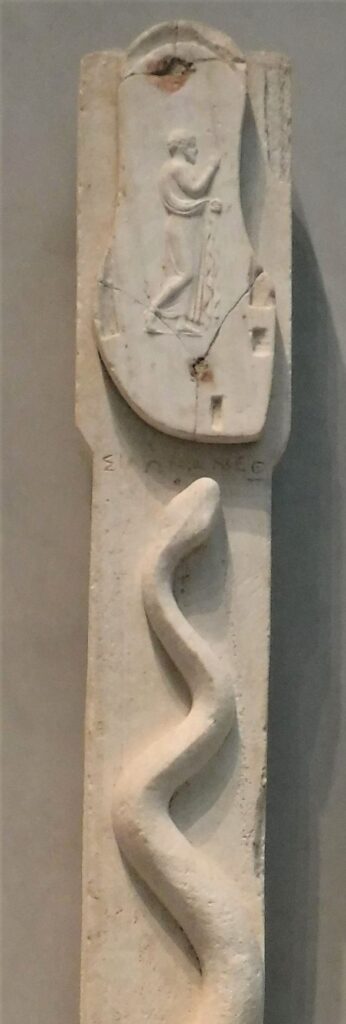

The Museum’s breathtaking number of artefacts were removed from the many buildings found on the slopes and summit of the Acropolis. They include pieces from the Sanctuary of Asclepios, which was located on the mount’s southern slopes. Asclepios was the God of Medicine, Health, and Overseas Conference Junkets. In ancient times, the ill and infirm would camp within his Sanctuary, waiting to be healed by the appearance of Asclepios in their dreams. Presumably some had to wait a considerable length of time, or all of the time they had left.

The stele exhibit on the left is titled ‘The Cult of the Hero on Blaute. Dedication.’ The Hero in question is the bloke carved into the sandal (blaute) at the top of the artefact. According to the Museum: ‘The interpretation of the scene is not certain. Some associate it with the cult of the Hero on Bloute on the south slopes of the Acopolis, and others with the Sanctuary of Blaute in the west‘.

A cult about a hero on a sandal? A Sanctuary of Sandals?? Drawn by an understandable fascination with this mysterious depiction of a hero upon a humble and ubiquitous piece of footwear, I did a little further research. It appears that the preeminant work on the Hero on a Sandal was published by G.W. Elderkin of Princeton University, way back in 1941. I read Eldo’s seven page treatise on the subject, and have to admit I found it all bloody confusing.

One theory he presents regarding the cultural providence of the stele, concerns a statue of Aphrodite, Pan and Eros. In this sculpture, Pan is lustily grabbing Aphrodite, keen for a little lovin’. She is clearly not up for some half-man-half-goat action, as has a sandal in her raised hand as if threatening to strike Pan.

There exists a remarkable parallel between this part of Greek mythology and the place of the thong in modern Australian culture (that’s a flip flop for our non-Australian readers). The thong is the modern equivalent of the Greek sandal, and often used to by Aussie mums to whack disobedient or unruly kids on the arse. Although many years separate ancient Greece and modern Australia, we are so closely linked by shared humanity, the need to protect our soles, and the weaponisation of footwear. Fascinating. Anyway, it’s probably time to move on…

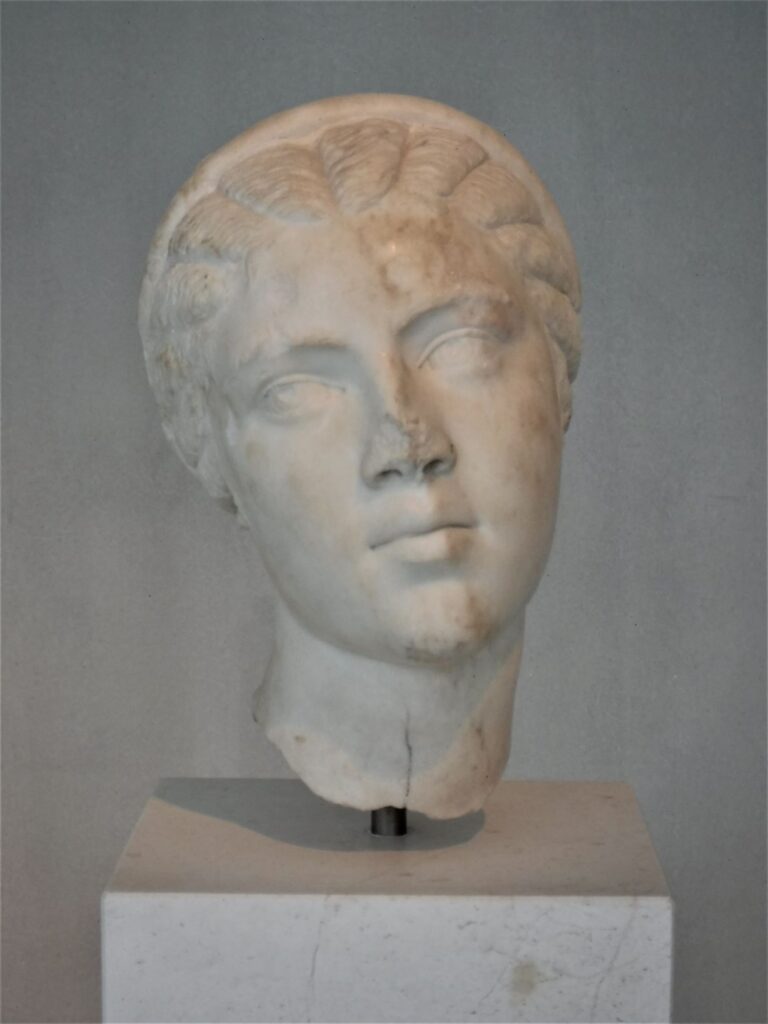

After spending an hour in the Acropolis Museum, I began to consider myself, not unreasonably, as a bit of an expert on Classical art. I have identified three categories of sculpture that I have no doubt will stand up to peer review.

There’s the ‘Look-away’…

The ‘Tilt’…

And the ‘Downcast’.

Creating sculptures without heads also seemed to be common in ancient Greece, and the Acropolis Museum held many examples of this unusual style.

A group of avant-garde sculptors took the ‘Headless’ school of art to the extreme, creating works without any body at all.

In Greek mythology, Nike is the Goddess of Victory (in modern times, Nike is the God of Child Exploitation and Slave Labour), and she is well represented in the ancient art that was found on the Acropolis. Many statues portray the Gods doing various godly deeds by means of suitably godly power. This sculpture is known as ‘The Sandalbinder, and shows Nike adjusting her sandal.

Although chariot design in ancient Greece was fairly rudimentary, mechanically-minded Athenians already had a eye for the future. At the annual Athens Chariot Show, sculptors and engineers presented concept vehicles, like this futuristic sedan.

On the north side of the Acropolis mesa stands the Erechtheum, the temple of Athena. Athena was the mighty Goddess of War, Wisdom and a Variety of Handicrafts including, I believe, macramé, decoupage and scrapbooking. She was also the patron deity of Athens, and gave her name to the city (more on this later). One of the most striking pieces of architecture on the Acropolis is the ‘Porch of the the Maidens’ which forms part of the Erechtheum. The roof of this structure is supported by six ornate statues, known as Caryatids, rather than your classic Greek columns. The original statues, well five of them at least, were removed from the Erechtheum in the late 70s over concern for their preservation. They were replaced by replicas, and the five original Caryatids are now displayed in the Acropolis Museum.

The other Caryatid had already been removed in 1804 by Thomas Bruce, Lord of Elgin. Thomo, a Scottish bloke, was Great Britain’s Ambassador to Constantinople from 1799-1803. Greece was part of the Ottoman Empire at this time, and Thomo received permission from the Sultan to undertake ‘research’ on the Acropolis. Much like Japanese whale ‘research’ includes killing a bunch of whales to ship off home, Thomo’s ‘research’ included lifting a substantial number of the Acopolis’ ancient treasures and hauling them off to Britain. Back in the UK, Thomo had the arse out of his strides*, so he flogged all the artefacts to the British Government who put them in the British Museum. So that’s where the other Caryatid ended up, separated from her five sisters. I know that’s just what you did in those days, but it’s still shithouse.

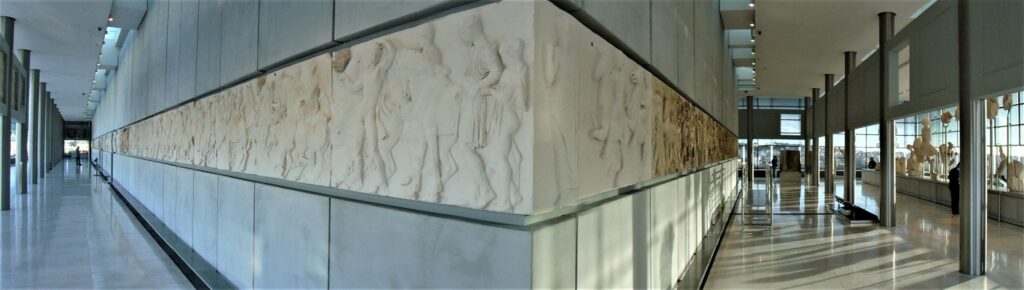

The top floor of the Acropolis Museum is dedicated to the sculptures that adorned the Parthenon; the grand-daddy of all the structures built on the Acropolis.

Similar to the Caryatids, much of the ornamental work from the Parthenon was removed to ensure its preservation, at least what was left after centuries of wear and tear and the nimble fingers of Thomas Bruce had nicked a bunch of stuff. From the Museum you can see the Parthenon atop the Acropolis.

The Parthenon frieze, which ran for 160 metres around the building, depicts the procession associated with the Great Panathenaic Festival.

The eastern and western pediments of the Parthenon were decorated with intricate sculptures of the gods. The ravages of time and that kleptomaniac Thomo hasn’t left much of these artworks behind. The east pediment is looking a little patchy.

Thankfully the Museum has provided a small-scale reconstruction of the pediment, showing it as it would have appeared in Acropolis’ heydey. It certainly would have been impressive.

Dionysis was one of the most popular gods in Ancient Greece, and not surprisingly, as he was the first rock ‘n’ roller. According to the Acropolis Museum, Dion was the God of ‘Wine, Inebriation, Ecstatic Dance’, and perhaps a little strangely, ‘Vegetation’. As he loved the fizz, presumably Dion spent a great deal of his time in a vegetative state, however I expect this title has more to do with vines, fruits and nature’s bounty generally. Anyway, the most important sanctuary, or place of worship, for Dionysis was located on the southern slope of the Acropolis.

Dionysis features in the east pediment panoply, his statue having been recreated for the Museum’s exhibit. True to form, Dion has been on the turps and is legless, unable to get up, his right arm is positioned to hold his beverage. Considering his lifestyle choices, it must be said that Dion’s physique is pretty impressive.

It had been a big first day exploring the treasures of ancient Athens, and it had certainly whetted my appetite to climb the mount and explore the Acropolis.

*Australian slang term meaning ‘broke’

If you liked this post, you may also like Bull Leaping, Exploring Ancient Petra

Visit the Acropolis Museum

Leave a Reply