‘Lost summers, without games or laughter…the sound of shells, bloody pavements, fire in the sky, sleepless nights. Waiting for better times.’ Lejla, six years old when the siege of Sarajevo began1

When I was a kid I loved watching the Olympics. Summer Games, Winter Games, it didn’t matter, there I was cheering for the Aussies and revelling in the mantra of ‘Faster, Higher, Stronger’. That was the first time I heard of Sarajevo, the city that hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics. The second time Sarajevo came to our screens in Australia was not for the celebration of nations coming together for sporting competition. It was for a long and bloody siege that mocked any notion of human rights and dignity.

I nearly missed the bus from Belgrade, after being short of cash for my ticket when I discovered the booking agency didn’t take card. I was relieved to make it onto the coach, and shortly after I flopped down into the seat we pulled out of the bus station on our way to Sarajevo. After crossing the Drina River, which forms much of the border between Serbia and Bosnia Herzegovina, we began to climb. Up into the range we went, eventually crossing the snowline, which afforded some beautiful views.

It wasn’t long after entering Bosnia Herzogovina that I noticed the war damage. Farm and village buildings with holes blown through walls, and pock marks from lighter weapons. Amongst the serenity of the mountains it was stark and confronting.

It was late afternoon by the time we arrived in Sarajevo, and the light was fading when I reached my accommodation on the Miljacka River. Big fluffy snowflakes were falling across the city.

I planned to spend the next few days exploring Sarajevo. As I cooked a meal in my apartment that first night, I didn’t realise how confronting, heart-breaking, at times incomprehensible, at times uplifting, my visit would be.

Sarajevo is a pretty place. Nestled in a valley and surrounded by the Dinaric Alps, the city’s architecture reflects its historic cultural and religious diversity.

Walking around Sarajevo, the physical scars of the Bosnian War are still clearly visible. During the conflict, the city was besieged by Bosnian Serb forces from 5th April 1992 until 29th February 1996. That’s 1,425 days, or nearly four years.

The Bosnian Serb ring of steel around Sarajevo averaged one piece of artillery every 35 metres, and fired an average of 320 shells per day into the city2

Some buildings have been repaired, whilst some have filled but unpainted holes that appear as light grey patches on the walls. Others sit untouched since the time they were hit by indiscriminate fire from the surrounding hills and mountains.

Walking the streets, you come across striking and poignant memorials to the victims of the siege: the ‘Sarajevo Roses’. In locations where artillery shells killed at least three people, the damage to the pavement has been filled with red resin.

Near the city centre, I paused by one of the roses (there are around 200 in Sarajevo), and took my camera from my backpack. An older gentleman was passing by, and he stopped by the rose and looked up at me.

Our eyes met, and he nodded. I nodded back, and he turned and continued on his way.

During the siege of Sarajevo, 11,500 lives residents were killed, including 1601 children, and a further 56,000 were wounded3

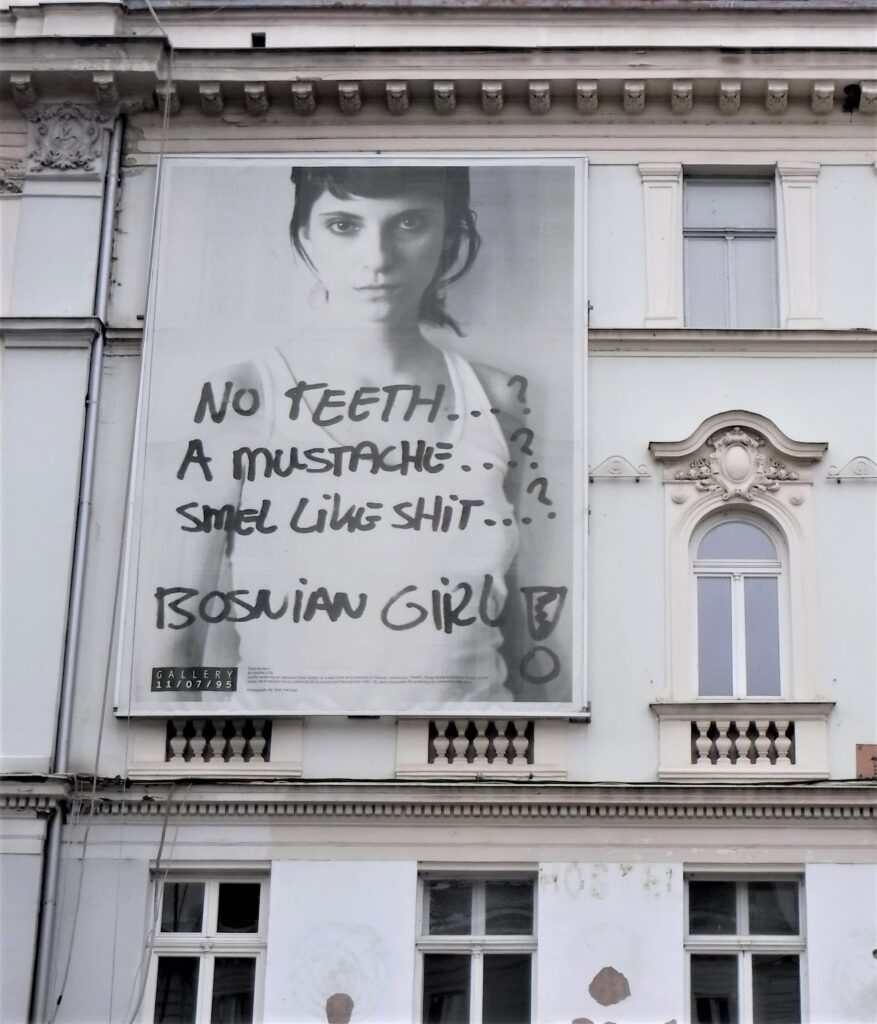

High on the wall of a building near the centre of town is a large billboard, featuring an image of Bosnian artist Sejla Kameric. It looks like a picture of a model from a fashion shoot. Crude black graffiti is superimposed across the image; mis-spelt English words form a derogatory, racist, misogynist slur. They are the words, and the handwriting, of a Dutch United Nations Peacekeeper stationed in Potocari, a short distance from the site of the massacre at Srebrenica.

‘Here we are on July 11, 1995 in Serb Srebrenica. On the eve of yet another great Serb holiday, we give this town to the Serb people as a gift. Finally…the time has come to take revenge on the Turks in this region.’ Bosnian Serb Army Commander Ratco Mladic after the taking control of Srebrenica4

The poster promotes Gallery 11/07/95, a visual memorial to the victims of the Srebrenica massacre. On that date, ‘Bosnian Serb militants overran a UN-established safe zone in Srebrenica, seperated about 8000 Muslim men and boys from the women who had sought shelter in the area, led them into fields and wharehouses in surrounding villages, and massacred them over the course of three days‘.2 The dimly lit black walls of the first room within Gallery 11/07/95 displays portrait photos of several hundred of these victims.

One of the most haunting images within the Gallery is a photograph by Tarik Samara, a Bosnian who lived through the siege of Sarajevo. Is shows the exhumed body of a victim of the Srebrenica massacre appearing to grip the gloved hand of a forensic worker. Within it I imagined a plea to ‘tell my story’. It is an acutely intimate image; depicting the comforting and uniquely personal gesture of holding another’s hand.

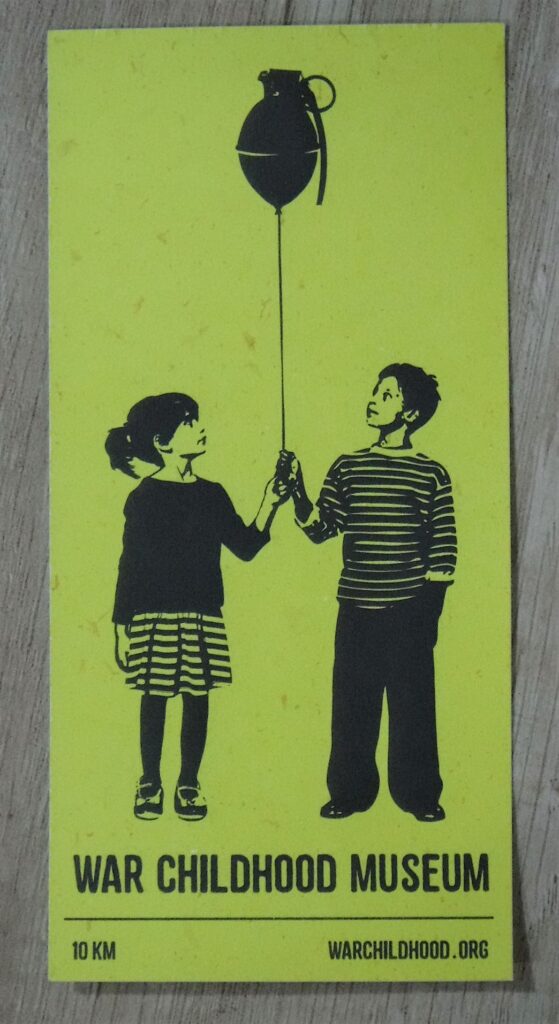

Not far from Gallery 11/07/95 is the War Childhood Museum. The founder, Jasminko Halilovic, collected the stories of Bosnians who had spent some of their childhood years during the war. This lead to the book titled ‘War Childhood’, which reproduced over a thousand of these short stories. Hallilovic was moved to preserve not only these oral histories, but also tangible items that held memories and meaning to those who grew up during the Bosnian War.

‘The image of a little girl carrying chocolate out into the snow to lay on her brother’s grave, because she doesn’t understand he’s not there anymore.’ Lejla, ten years old when the siege of Sarajevo began1

The result of Halilovic’s passion and drive is the War Childhood Museum. It is the only museum I have ever visited that provided a box of tissues for visitors. I know I’m not the only one who made use of them.

Amongst the stories is that of Kemal, accompanied by a military boot. Kemal explains that the boot belonged to his brother, who at 16 volunteered for the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

‘I entered the house a couple of moments before the mortar shell hit, and that is the only reason I survived. My brother Kenan and my grandma died on the spot. My sister was wounded in the head. The doctors who operated on her couldn’t save her life. Killing innocent people was the intention.’

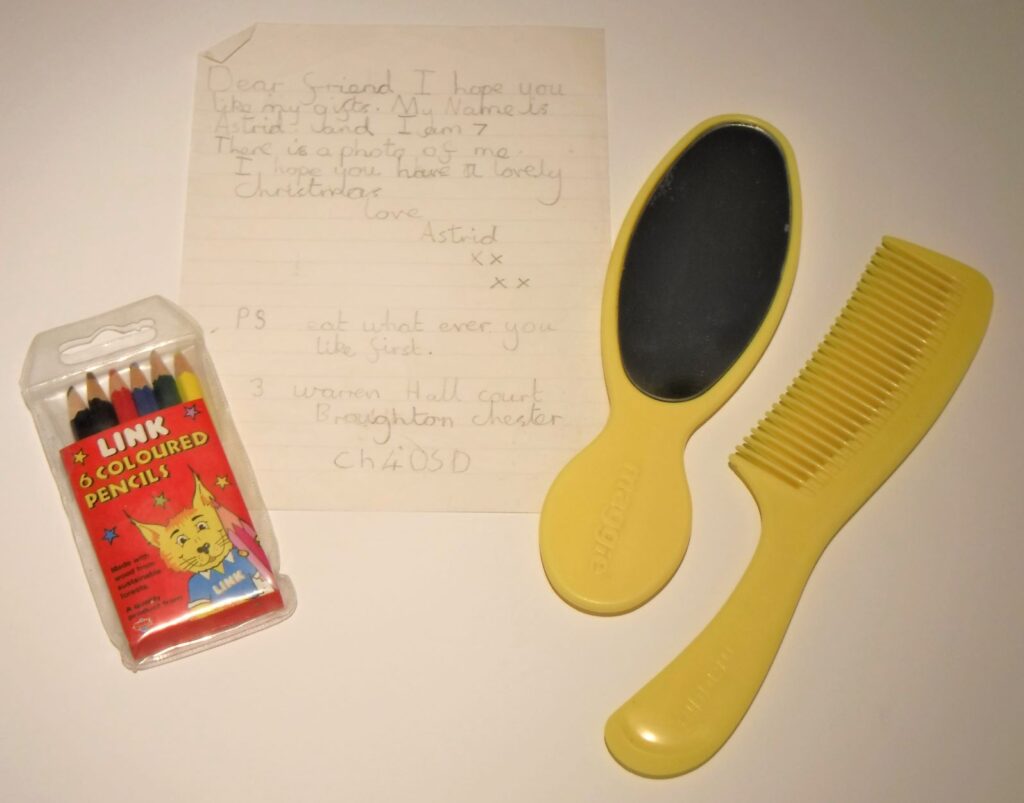

Lejla wrote: ‘…the children of Cazin received little care packages. I remember my excitement as I approached the house that was in charge of distribution. The shoebox was colourfully decorated. The package had toiletries, candy, and a photo and letter from Astrid‘.

The sender, Astrid from England, wrote: ‘Dear friend, I hope you like my gifts. My name is Astrid and I am 7. There is a photo of me. I hope you have a lovely Christmas. Love Astrid. P.S. Eat whatever you like first‘.

Lejla continued: ‘That gift was part of my daily life for a long time, as were the comb and mirror part of my makeup bag. I never used the colours because I did not know how long the war would last and I did not want to run out of them.’

A kind gesture from a stranger in another country; from a little girl at peace to a little girl at war. It made me wonder at what age kids grow up and learn to hate.

The Museum of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity has a unassuming entrance off a street in downtown Sarajevo. I have visited many places across the world that stand as memorials to some of the darkest chapters in human history, but I have to say this museum was one of the most confronting and disturbing I have experienced.

The accounts of brutality and ‘inhuman’ savagery that are documented within left me shocked. The Museum pulls no punches; it is an unabridged, uncensored display of the Serbian nationalists’ unabashed cruelty. (Although wholly incomparable with the genocidal atrocities carried out by the Serbs, former Bosnian soldiers have also been charged with war crimes.)5

‘In only one day, at least 265 villagers from this village (Biljana) were killed by members of the police and Army of Republika Srpska. The oldest victim…was 85 years old, and the youngest…was a four-month old baby’2

A video was playing on loop, and I took a seat in a room whose walls were covered in ‘post-it’ notes, each one with a message written by a visitor. I watched as Sarajevo residents, clutching loaves of bread, dash across the street in fear of being sniped. The older men reminded me of my Dad. In order to protect civilians from being shot whilst leaving their homes for essentials, French peacekeepers create a sheltered line using shipping containers. After placing a container in line, the French soldier driving the forklift is shot in the head.

The Museum included a photo of a boy on a sleigh, clutching water containers. During the siege, Sarajevo struggled without power, gas or running water. Residents, including children, risked their lives to collect water from the scarce wells within the city.

After reading accounts of massacres, rapes, and unspeakable horrors within concentration camps, I was left wondering how people who have lived side-by-side for so long could suddenly turn on their neighbours with such unrestrained barbarity.

Having worked my way through the Museum, I asked the staffer, a bloke in his late 30s/early 40s, about this. I said that there must have been deep underlying issues within the society, as the desire to unleash such unimaginable cruelty cannot just appear overnight. He said that once an environment had been created where atrocity was sanctioned, those within the community that harboured violent or psychopathic tendencies had free reign to act with impunity.

I told him that I couldn’t understand how Bosnia Herzegovina can exist today when in recent history there was such hatred and violence. How can you just go back to living together after what happened between 1992-1995? Don’t people walk down the street, and wonder if the middle-aged man they just passed was a perpetrator of war crimes, or stood by as they were committed? The staffer told me that the perpetrators were put on trial and imprisoned. I said there must still be many rank and file soldiers out there amongst the community that were guilty of atrocities. He seemed to take offence at my comment, and answered that in Australia I could also be passing murderers in the street.

I hadn’t meant to cause offence, or imply that the population of Bosnia Herzegovina were a bunch of butchers and savages. I just couldn’t believe that as war crimes were committed at such a grand scale, all those who were guilty had been identified, tried and convicted. We talked for quite a while until some more visitors arrived and were waiting to buy tickets. I thanked the staffer for his time and insights, and started down the stairs.

My experience in the Museum had been so intense that I suddenly felt an urgent need to get outside. I know it sounds strange, but I had an irrational need for reassurance that everything was ok. That what was portrayed in the Museum was not what was happening right now out in the street. That people in Sarajevo today were just going about their daily lives without fear of snipers, mortars, or being rounded up and sent to their deaths. I hurried down the spiral steps, pushed open the door, stepped into the cool of the late afternoon, looked around me, and breathed a deep sigh of relief.

‘The Tunnel is always going to represent the door between life and death, in the heart of Sarajevo there is the major lifeline soaked with blood and tears, but triumphantly proud‘3

The shortest distance between besieged Sarajevo and free Bosnian territory was across the city’s airport. Although the UN were in ‘control’ of the airport from July 1992 (the facility was still sniped and shelled by Serb forces), only humanitarian aid was permitted to be brought in by plane, and Sarajevo citizens were not permitted to leave. In order to evacuate wounded soldiers and civilians, allow residents to flee, and bring in materiel for the defence of the city, the Bosnian Army tunneled from beneath a house in besieged Sarajevo, under the airport, to a house in the free territory on the other side.

On a freezing winter’s day I visited the Tunnel of Hope Museum, which incorporates the house beneath which the tunnel was dug. A newly built display area showed footage of life in the city under siege, and the construction, using only hand tools, of the Tunnel.

‘When I came out to the other side, firstly I was overwhelmed by an incredible feeling of freedom. At that moment we were under the siege for almost a year and a half‘3

‘…every return to Sarajevo was a return to Dante’s Ninth Circle of Hell’3

A section of the Tunnel had been preserved, and as I stooped to pass through the narrow space, I tried to imagine what it would have been like to traverse the entire 785 metre (the actual tunnel, plus the covered trenches at either end) passage.

Simple make-shift tracks of angle iron permitted transport carts to be pushed through the Tunnel.

My time in Sarajevo exploring the recent history of Bosnia and Herzegovina had been a jarring juxtaposition of past horrors and the beautiful, and seemingly peaceful, present-day city. I had certainly learnt a lot, and yet still could not find answers to many gnawing questions. Most troubling of all was hearing from residents of Sarajevo that Serb nationalism is again on the rise. Less than 30 years since the Dayton Peace Agreement, and after so much suffering, surely Bosnia and Herzegovina couldn’t plunge back into civil war. Could it?

1Halilovic, J., 2013, ‘War Childhood‘

2Museum of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Sarajevo

3Tunnel of Hope Museum, Sarajevo

4Suljagic, E., 2020, ‘How the Bosnian Serb Assembly Redefined Bosniaks as Enemy ‘Turks’, Balkan Transitional Justice, BIRN

5Euronews, 2021, ‘Bosnia arrests five former Muslim Soldiers for war crimes against Serbs‘,

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy Red Cross Concentration Camp, Strange Meeting

Leave a Reply