I climbed the stairs out of the U Bahn (underground city rail network) and popped out into the cool, overcast afternoon. Soon I was part of the jostling crowd of tourists surging along towards the site of Checkpoint Charlie. I had been a bit crook so hadn’t left the hotel for a couple of days, and to be honest I felt a bit overwhelmed by all the poeple, noise and clamour.

During the Cold War, Checkpoint Charlie was a throttled conduit between the East and West. It was a place of hubris, tension and tedium, of protest riots, escape attempts and state-sponsored murder. In late 1961, it hosted a flashpoint confrontation between the superpowers, when Soviet and US tanks faced off across the border.

Today, Checkpoint Charlie is a circus. A replica of the checkpoint stands in the middle of Friedrichtstrasse, surrounded by international fast food and cafe franchises. Garishly painted double-decker tour buses lurch along the narrow lanes, and groups of tourists on scooters, pushbikes and segways dodge in and out of the pedestrian crowds. Souvenir stands stock faux Russian bear skin hats, replica soviet-era uniforms, t-shirts and plastic gas masks. Seemingly unaware that the street is a through passageway for vehicles, tourists wander and mill about on the road, provoking the horns of motorists.

They swarm around the small sentry box and sandbagged memorial plaque, getting in each others’ way as they pose and gesticulate for holiday snaps. It’s as if they’re having their photos taken at Disneyland.

The plaque reads: ‘To commemorate the tank stand-off at Checkpoint Charlie on 27th October 1961 and in gratitude to Lt. General Lucius D. Clay, Berlin envoy of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, for his resolute action in defending the freedom of Berlin’.

I watched one young woman, dressed up for a night out, pose in front of the plaque with an open beer bottle, as if doing a promo for the brew.

Considering the history of the place, it all seemed a bit off.

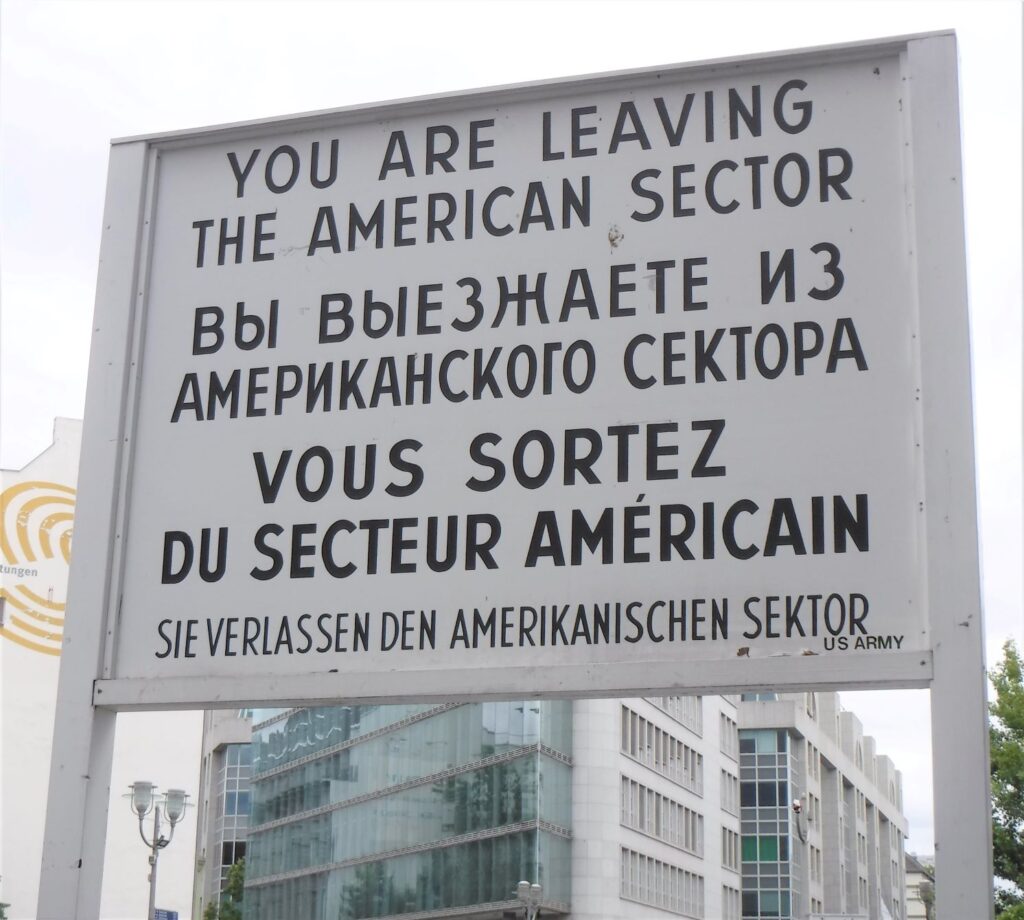

Replica sign at the Checkpoint

I waited for ages until I could secure a clear picture of the Checkpoint and then retreated to the footpath. Looking down Friedrichstrasse, I tried to imagine the two columns of tanks facing one another during the 1961 standoff. In all the afternoon crowd and noise and tat, I couldn’t.

A few metres down Zimmerstrasse (which intersects Friedrichstrasse a few metres north of Checkpoint Charlie) I have my first contact with the Berlin Wall. The position of the structure which gave physical form to the political divide between East and West Berlin is marked by two rows of inlaid stone blocks.

The brass plaque reads ‘Berliner Mauer 1961-1989’

Relieved to be away from the crowds, I made my way down Zimmerstrasse to the Peter Fechter memorial. Peter was 18 years old when he and a friend tried to escape from East Germany to the West. East German border guards shot Peter several times (his friend made it across the wall), and in an act of gross inhumanity, left him bleeding at the base of the wall for nearly an hour. As the incident occured on the East German side, West German guards and Allied personnel from Checkpoint Charlie could only watch on helplessly.

Members of the public also witnessed the horrifying scene. Margit Huessini stated: ‘It was a traumatic experience for all of us, watching that young man there and hearing him scream for help. At first they were perfectly normal cries for help. Then he started to plead and he got quieter and quieter, as if his life was gradually seeping out of his body. It was terrible, really terrible.’1

‘…he just wanted freedom’

By the time East German border guards carried away the crumpled form of Peter Fechter, he was dead.

I headed back towards Checkpoint Charlie, then continued west along Zimmerstrasse. About five minute’s walk and I arrived at one of the remaining standing sections of the Berlin Wall.

Rearing up from the roadside, the Wall was monochrome, stark and rough, yet thinner in profile than I imagined. In parts the outer concrete veneer remained intact, providing a glimpse of what the entire 155km long human rights abuse would have looked like. (43km of wall separated East and West Berlin, whilst the remainder cordoned off West Berlin from broader East Germany). In others, rusty steel reinforcing rods were bared liked ligaments in an open wound.

I walked the length of the remaining section, trying to imagine waking up one morning, looking out the window, and finding this monstrosity under construction. There was no Checkpoint Charlie tourist crush here at the Wall, and gratefully none of the associated industry. The relative quiet permitted space for contemplation.

On the eastern side of the wall is the confronting wire-cage architecture of the ‘Topography of Terror’ museum. During the time of the Nationalist Socialists, this site housed the headquarters of the Gestapo. Below street level, beside the remains of basement brickwork, information panels describe the rise of the Third Reich, and the experience of the city of Berlin during World War II. This exhibit was popular, and I shuffled along with the crowd, reading about the 12 years of terror that happened here before the new, post-war wave of state control arrived.

Being still a bit under the weather, I was beginning to wilt. But I wanted to visit one more site before I headed back to the hotel. Watchtowers are a poignant symbol of autocratic regimes; blank concrete and one-way glass, where agents of the state watch not for external threats, but rather surveil their own citizens. After a short walk from the Wall I reached one of the remaining towers. It stood within a construction site, so I could only view it through, and over, a security wall. This seemed apt, especially as barbed wire topped the barricade.

My energy spent, I returned to the subway and waited for my train home. I had found my visit to the Berlin Wall fascinating and unsettling. Although I couldn’t reconcile the tourist carnival of Checkpoint Charlie with the gravity of what had occurred there during the Cold War, the remnant of the Berlin Wall was a chilling reminder of the consequence of placing social theory and political ideology above human dignity.

1The Berlin Wall, A Multi-media History, ‘Peter Fechter Dies Trying to Escape‘, quote from an interview with Margit Huessini

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy Stasi Bunker Museum, House of Leaves

Do you have a particular interest in World War I, II and the Cold War? Check out my other blog Ghosts of War. If you enjoy military history, and want to know what it’s like to visit both significant and lesser-known wartime locations today, there’s something there for you.

Leave a Reply