It was one o’clock in the afternoon when we pulled up beside V.C. Corner Cemetery, near the small village of Fromelles in northern France. It was cold and drizzling rain, and the gloomy light made it feel much later in the day. We were the only visitors.

We made our way though the gates and onto the lush, wet grass. Six large trees border the edge of the cemetery, and were sporting fresh, early spring growth. Beyond lie neatly cut beds of rose bushes; no buds had dared to emerge from the long northern winter.

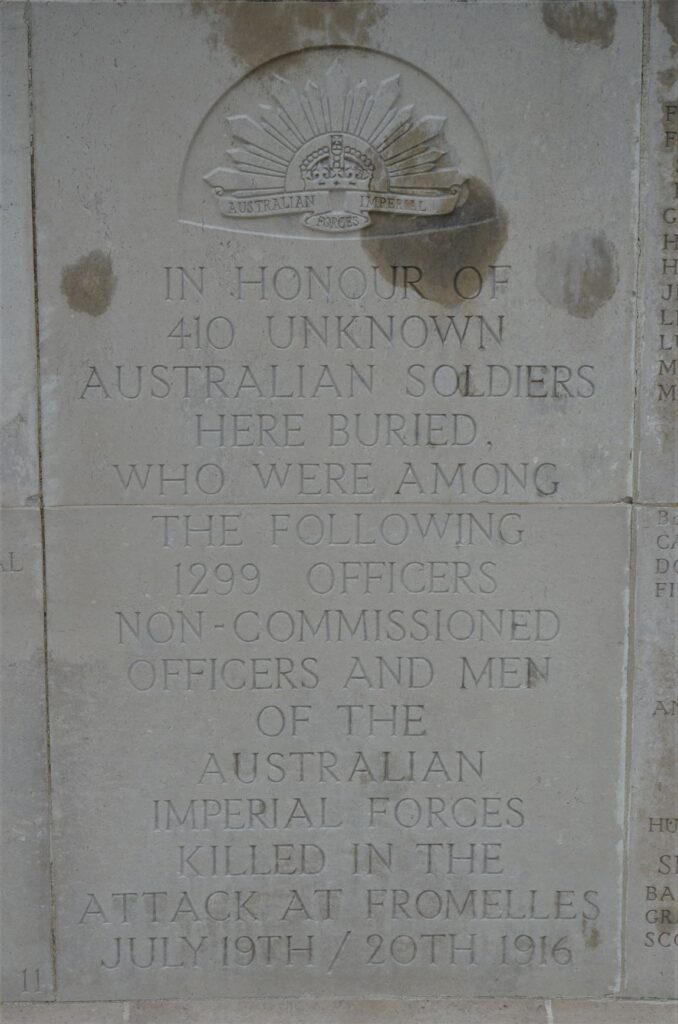

Unlike many other Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries, there are no headstones at V.C. Corner. Interred within the cemetery are the remains of 410 Australian soldiers who died at Battle of Fromelles on July 19-20, 1916, but whose remains could not be identified.

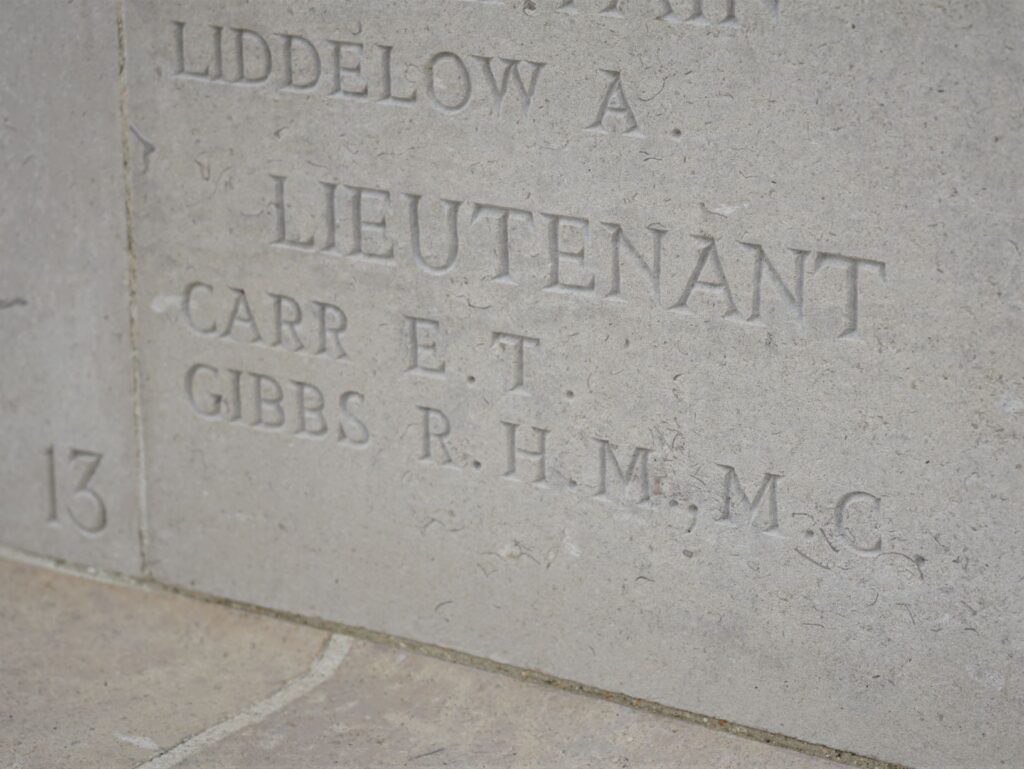

We approached the memorial at the northern boundary of the cemetery, which is comprised of an elevated cross, and two small chapels linked by a wall. On the wall are engraved the names of those Australians who lost their lives during the Battle of Fromelles, but have no known grave. Tracing horizontally along the list of Battalions involved on July 19-20 1915, we found the 59th. Names were listed under ranks; first Captain, then Lieutenant. Under Lieutenant, our eyes fell to the second name listed: Gibbs, R.H.M., M.C.

Mac.

Our ancestor Richard Gibbs and his wife Helen (née Maconachie) had three sons, Richard, John and Angus. The eldest was Richard, whose third given name was Maconachie, and he was known as ‘Mac’. After growing up in Colac, 150km south-west of Melbourne, Mac was studying medicine when World War One broke out. At 23 years of age he left Melbourne University and enlisted in the 6th Battalion, Australian Imperial Force.

A handwritten note on the back of this photo reads ‘Mac in camp at Castlemaine’

A week before turning 24, Mac left Australia for Egypt, where further training would prepare the Australian forces for the battlefields of France. Transferred to the 59th Batallion, he was destined to take part in the Battle of Fromelles, a feint attack designed to prevent the Germans reinforcing their positions on the Somme.

When I was a kid, primary school age I reckon, I remember Dad talking to me one afternoon in the hallway of our old house. It was a long hallway, and always a little dark and gloomy as it had no external windows. Bookcases lined one side, filled with old hardback books which had yellowing pages and a faint musty smell. Many of the books had family names hand written in blue fountain pen on the title page, and maybe I had asked Dad about one of the names. Dad was always keen on family history, and if you asked him about it you were likely to receive a very detailed and lengthy answer. Anyway, that day Dad told me about Richard Gibbs’ son ‘Mac’, and that he had been killed in France. I couldn’t really understand it all at that age; they were just the names of long gone ancestors, and places far away on the other side of the world.

But now I was standing in light rain, looking over the ploughed paddocks to where the front line had been on July 19-20, 1916. The Australians and British attacked the heavily defended German lines over a four kilometre front, and somewhere to the south-west of where I stood, Mac had waited in a trench for the order to attack. What happened next was detailed in Mac’s Military Cross citation:

‘..when his Company Commander was seriously wounded immediately prior to the order to charge Lieut. Gibbs took charge and led his men over the parapet. By his example the men were spurred on, and although advancing under a galling machine gun and rifle fire he kept his men moving steadily forward in perfect line and order. Lieut. Gibb’s calm and collected manner gave his men the impulse necessary to carry them as far as it was possible to go.’

The attack was a disaster. After 24 hours, the Australians had suffered 5533 casualties, nearly 2000 of which were killed in action or died later of their wounds. One of the men who did not survive that awful day was Mac.

Perhaps Mac is lying beneath the soft grass of V.C. Corner Cemetery, alongside the other unidentified young men whose lives were cut so tragically short at Fromelles. Or maybe he is still somewhere along the line of no-man’s land, then a nightmarish place of violence, carnage and suffering, but today a quiet area of paddocks and farmhouses in rural France.

My sister and I placed a small memorial cross and poppy beside Macs engraved name, sitting awhile by the memorial wall. Like Mac and the other Australians at V.C. Cemetery, we are thousands of miles from home, in a place which will be forever marked in our family, and our national, history. When we attend the ANZAC Day service tomorrow at Villiers-Brettoneaux, we will remember Mac, his brother Jack whose life was also claimed by World War One, and all those who served.

Lest We Forget.

Find more about V.C. Corner Cemetery here

If you like this post, you may also like El Alamein War Cemetery, Honour Them With Peace

Do you have a particular interest in World War I, II and the Cold War? Check out my other blog Ghosts of War. If you enjoy military history, and want to know what it’s like to visit both significant and lesser-known wartime locations today, there’s something there for you.

Leave a Reply