Traces of war

Crete is characterised by miles of beautiful coastline, olive groves, and little villages set on the lower slopes of spectacular, rugged mountains. However, museums, memorials and cemeteries found across the island are testimony to the dark days of the Battle of Crete, and the determination of the Cretans to honour those that fought against the invaders during World War II.

With German and Italian forces sweeping through mainland Greece, the Allies were forced to withdraw, with the majority of troops evacuated south to Crete in late April 1940. British, Greek, New Zealand and Australian forces set up defensive positions on the island, knowing that it was only a matter of time before the Germans would invade the strategic outpost.1

I flew into Heraklion, the administrative capital of Crete, and spent a week exploring the town. Whilst walking near the town centre, I came across a monument with Greek, British, New Zealand and Australian flags flying. Brass cast plaques described the Battle of Crete, and stated that 17,000 British, 11,500 Greek, 7,700 New Zealand and 6,500 Australian troops were stationed on the island prior to the invasion.

Battle of Crete Victory Monument, Heraklion

The defence of Crete centred around Chania, Rethymno and Heraklion, the largest towns on the north coast of the island. Lieutenant James Carstairs, 2/7 Australian Infantry Battalion, wrote in his diary ‘…air raids were increasing in intensity day by day. Suda Bay (Chania’s port district) was being pounded unmercifully. The General (Major-General Bernard Freyberg, commander of the Allied forces) predicted an attack at any time‘.2 On 20th may 1940, German paratroopers dropped over the Allied positions, followed by more troops arriving by glider.

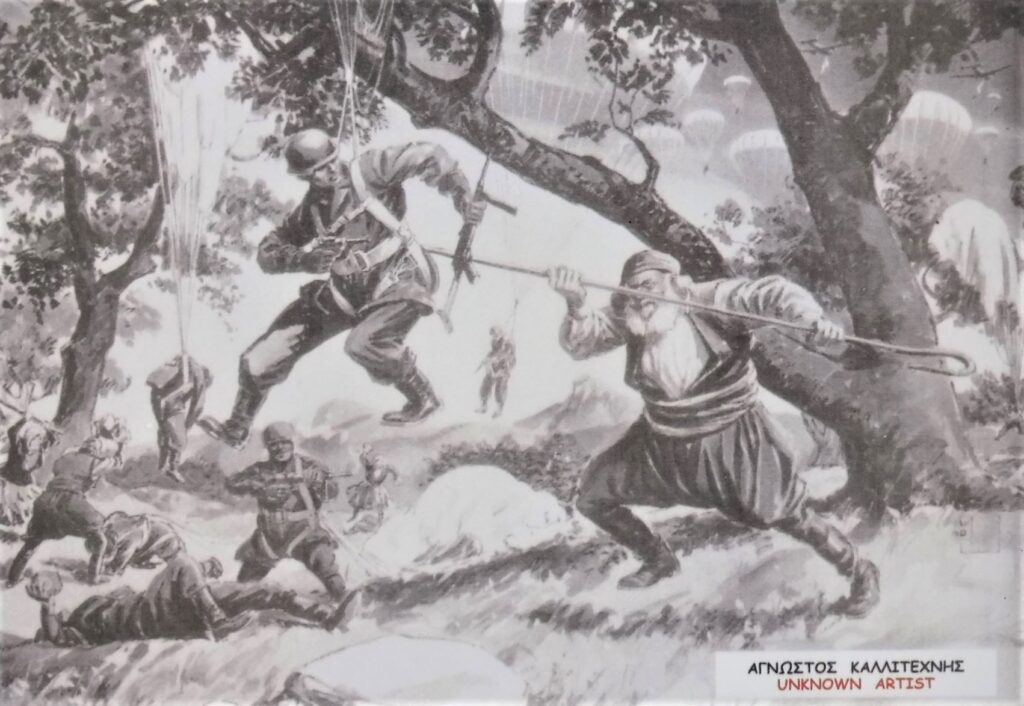

The Maritime Museum of Crete, located in Chania, has a large display on the Battle of Crete. Reproductions of artworks displayed in the museum show that local Cretans provided staunch resistance against the paratroopers.

Although initially withstanding the first wave of the attack, the German forces were able to capture Maleme airfield, permitting reinforcements and supplies to arrive by aircraft. The British, Greek, New Zealand and Australian defenders were forced to retreat.3

Maleme airfield is a military establishment today, and photographs of the area are prohibited. However you can make out the runways in the distance from the hillside German Military Cemetery of Maleme.

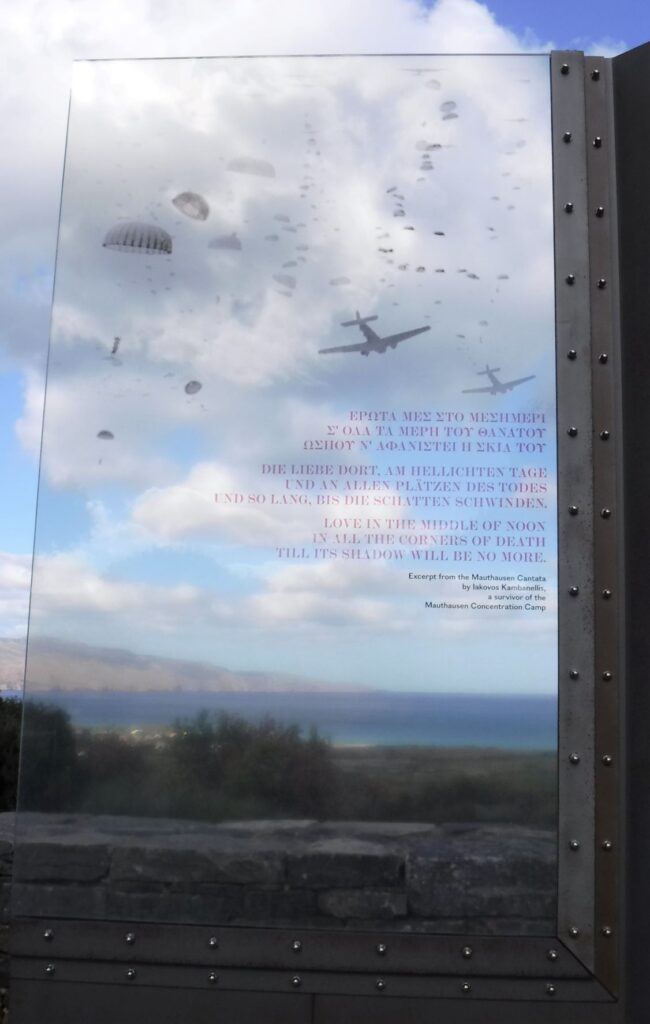

Interpretive panel, German Military Cemetery, Maleme

I visited the cemetery on a cold windy day, where the remains of 4,468 German soldiers are interred. The cemetery includes a small museum, where respectful, thoughtful and candid displays describe the invasion, its aftermath and the nearly four year Axis occupation of Crete.

On May 26th, Major-General Freyberg concluded that facing a reinforced and well supplied enemy with dwindling food and ammunition was a hopeless cause. The decision was made to retreat across the White Mountains and evacuate the Allied forces from the south coast of Crete.1

The Australians and New Zealanders based at Chania fell back and set up defensive positions along Tsikalarion Street, a country lane running pretty much north-south, located around five kilometres south-east of the city. To the Allies, Tsikalarion was known as ’42nd Street’, named after the British 42nd Field Company, Royal Engineers, who were stationed there. On the morning of the 27th May, 1941, German soldiers from the 141 Mountain Regiment approached the ANZAC positions. In a spontaneous act of bravery, Private Apouri from 28 (Maori) Battalion stood up and began to perform the haka. With fixed bayonets, the ANZAC troops charged the oncoming Germans with a ferocity that forced them to turn and retreat for more than a kilometre. This action allowed the Allied forces valuable time as they withdrew south across the mountains.4

I decided to dial up Tsikalarion Street on my phone’s map app, and go and have a look where the battle took place.

It was a bit of a hike from my apartment in central Chania, but the weather was fine and I enjoyed the exercise. On the way I saw an olive grove where ‘screw pickets’ (looped lengths of steel rod used during the war to install barbed wire defensive lines) had been utilised as fence pickets.

Screw pickets

I wasn’t sure if there would be any signs marking Tsikalarion Street as a significant site of the battle of Crete. However as I approached I knew I had the right place.

After photographing a map at the Maritime Museum of Crete, I decided to walk down the street as far as the ANZAC positions were spread. Although houses and businesses have been built along 42nd Street, and it is now sealed instead of being a narrow country lane, I imagined the citrus orchards and olive groves have changed very little since that fateful day in 1940.

Looking south down 42nd Street; Looking west, the direction from which the Germans approached the ANZAC positions

As I reached the southern limit of where the ANZACs had established their line, I found a memorial to the defenders of 42nd Street.

42nd Street Memorial

Although the British troops defending Heraklion were able to be lifted from their positions by navy ships under cover of darkness, for the remaining 16,000 Allied soldiers the small beach at Hora Sfakion on the south coast was chosen as the evacuation point.1

Being wintertime, I wasn’t sure whether the privately run Askifou War Museum, located in the village of Kares, would be open. Kares is located on the Askifou Plateau, which was crossed by the retreating Allies as they headed for the evacuation site at Hora Sfakia. I followed the hand painted signs through the village, and parked outside the Museum. When I climbed out of the car the owner greeted me, calling down from the balcony above.

The owner is Andreas Hatzidakis, whose father Georgios was a child when the Germans invaded in 1940. Georgios lost his childhood home, and his sister, in German air raids, and was himself badly injured. Experiencing the horror of the war, and witnessing the bravery and determination of the Cretans during the occupation, Georgios was inspired to start collecting war relics and artefacts. His desire was to create a lasting memorial to those who fought, died and suffered on Crete during World War II, and to ensure future generations learn about this part of their history. Andreas now manages the Museum after his father passed away.

British Norton motorcycle; German Stuka aircraft pilot’s seat left, British Spitfire right

Andreas guided me through his Museum, pointing out particular items of interest in what is an extraordinary collection. There was so much to see that after his tour I had to wander back slowly through the collection to take it all in.

German items, including Crete service armband

After a grueling march, and rearguard actions to delay their German pursuers, the British, Greek and ANZAC troops arrived at Hora Sfakia. Exhausted and hungry, they waited at the evacuation point for the ships to come.5

To be continued…

1Australian War Memorial, (2021) ‘Crete, Kreta: The Battles of May 1941‘, Australian War Memorial, Canberra

2Carstairs, J. de M. (1941) ‘Escape from Crete’, Society of Cretan Historical Studies, Heraklion, 2016, p30

3Information panel, Military Museum of Chromonastiri, Crete

4Information panel, 1941 Battle of Crete Anzac Memorial, Tsikalarion/42nd Street, Crete.

5Bastion, R.J. (2007) ‘Hora Sphakia’, information panel, Hora Sfakia, Crete

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like The Battle of Crete Part II, The Battle of Crete Part III, El Alamein War Cemetery, Searching for the Blockhouse

Learn more about the Askifou War Museum

Do you have a particular interest in World War I, II and the Cold War? Check out my other blog Ghosts of War. If you enjoy military history, and want to know what it’s like to visit both significant and lesser-known wartime locations today, there’s something there for you.

Leave a Reply