Two minutes to midnight

Ukraine is a big place by European standards, second only to Russia in land area. Factor in some serious mountains, major watercourses and a network of secondary roads that are potholed to the shithouse and it can take a long time to get from A to Б. So I figured that hiring a car would be the most efficient way to get around, particularly to the more out-of-the-way places I was keen to explore.

At Odessa airport, the car rental company staffer photocopied my passport and driver’s licence, and then ran through the paperwork with me. It’s the first time I have had to sign a rental agreement which included not taking the car into an area contaminated with radioactive material, or driving into either of two active war zones. Not wishing to be either irradiated or detonated I signed on the line and was soon punting my little Citroen sedan through the Odessa traffic.

During the years that Ukraine was part of the USSR, Russia shifted an enormous number of military assets into its southern neighbour. Literally thousands of nuclear weapons were stationed in Ukraine, including (by the end of the Cold War) 176 Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs). These weapons were the big bangers of the arms race; rockets that were launched into space and arced towards their targets more than 5,500km away at around 24,000km/h. ICBMs put the assurance in Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). They either made the world safer as neither of the nuclear Superpowers would dare to use them, or more dangerous as any cock-up would lead to Armageddon. Depends on who you talk to.

When the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991, work began on neutralising the nuclear arsenal that was scattered across Ukraine. ICBMs were removed from launch sites, and the control centres and missile silos destroyed. However the arms liquidators left one launch site intact, near the town of Pervomaisk in south-central Ukraine, to be preserved for the future. Today it is the Museum of Strategic Missile Forces.

I navigated the Citroen 220-odd km north of Odessa through undulating cropping country, arriving in Pervomaisk on a bright and cold afternoon. After stocking up with food, I settled in to my chalet-style motel unit, which, like the weather, had a distinctly Nordic feel. The following day I would drive the half-hour to the Museum of Strategic Missile Forces.

The next morning was overcast and sullen, and a cold wind blew across the paddocks of sunflowers, wheat and corn as I headed north to the Museum. Turning off the tar onto a minor road, it was hard to imagine I was heading towards what was once a major military installation which packed enough firepower to tip off the end of the world. That was the point, of course: to hide the missile sites away amongst the hundreds of thousands of square kilometres of Ukrainian farmland and forest.

I was the first visitor to arrive for the day, and after paying for admission I pushed open the door of the ticket booth and stepped into the museum grounds. A bloke in military uniform approached me, and explained that if I wished to tour the Unified Command Post (UCP) with an English speaking guide to let him know. I thanked him and said I would look around the above-ground display galleries first, and find him when it was time to venture into the UCP.

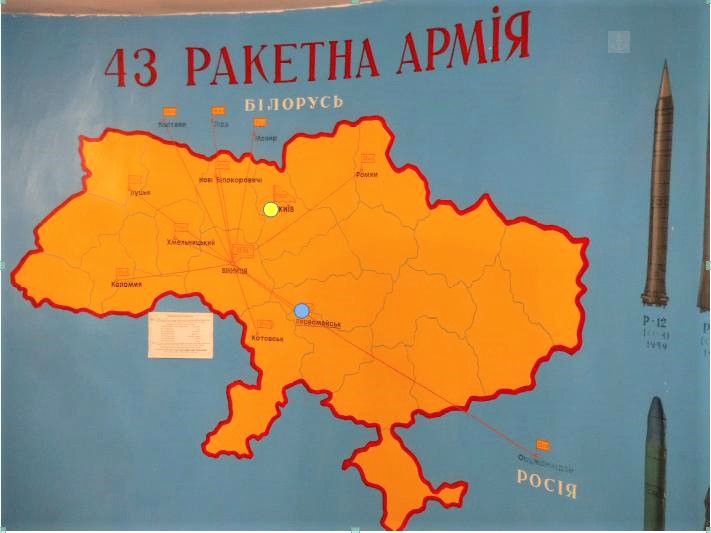

Inside the Museum of Strategic Missile Forces, a hand-painted map showed the location of the seven rocket divisions stationed in Ukraine, which formed the 43rd Rocket Army. The 46th Rocket Division based at Pervomaisk was responsible for 86 ICBMs. I’ve added a couple of dots for clarity: yellow is Kiev and blue Pervomaisk.

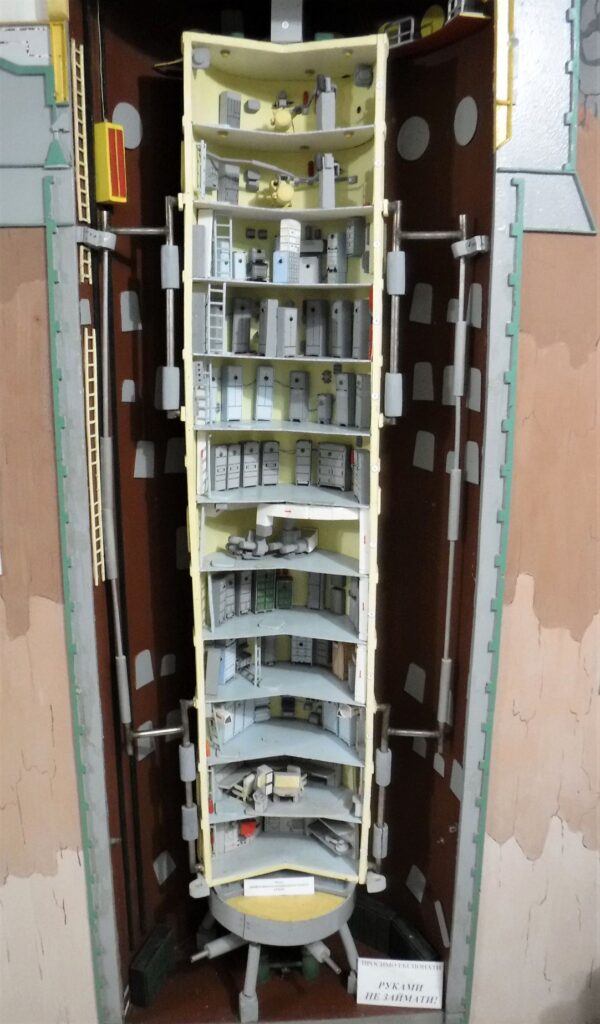

This model details the UCP, which is is pretty much a 33m long steel tube suspended inside a concrete-lined shaft dug vertically into the ground. Massive shock absorbers hold the UCP in place, and the whole set-up is designed to still be operational after a nuclear strike. Each level of the UCP contains technical equipment, with the control centre, where two officers were stationed at the launch desks at all times, located on the 11th level down.

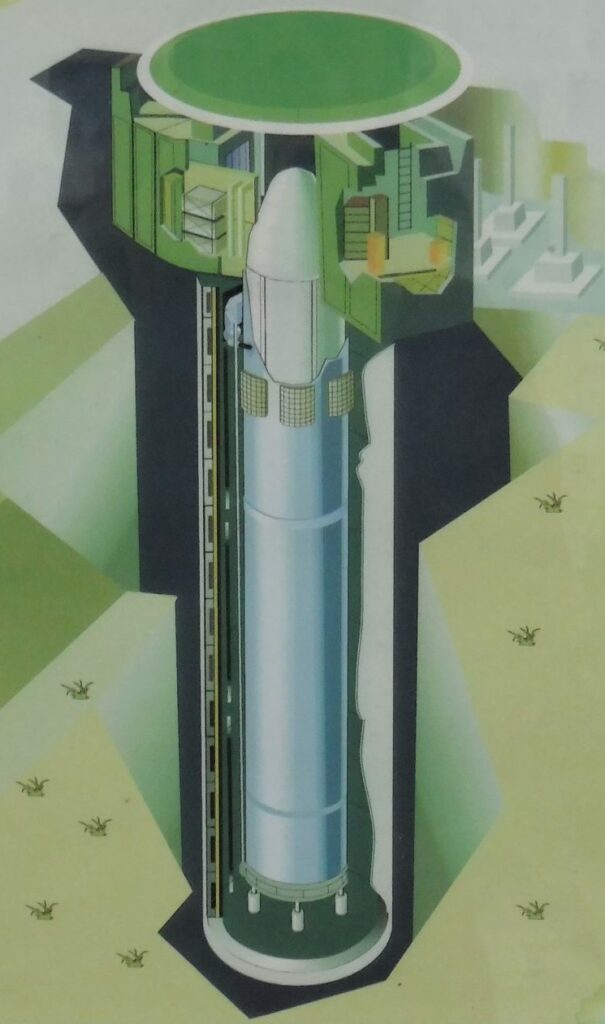

Also on display was an illustration of a missile silo, showing where the ICBMs were concealed. While walking around the gallery it is easy to get swept up in what was pretty remarkable engineering. A hi-tech control centre buried in the earth, and space-rocket missiles looking like something out of The Thunderbirds concealed in underground silos and ready to strike. However a gnawing unease accompanies this appreciation of the technology; this place had the potential to trigger the end of life as we know it, or potentially respond in time to incoming enemy ICBMs and thereby hold up the USSR’s side of MAD.

A full scale-model of the UCP launch level gave those visitors who were not going to venture underground a very clear idea of where the officers, tasked with a responsibility of unimaginable gravity, sat through their six hour shifts. In a nearby display case was one item I found particularly chilling: a red velvet-lined box containing a launch key.

Not only was the Museum of Strategic Missile Forces designed to educate, it is also a monument and memorial to the 46th Rocket Division. Displays commemorate the men who served at the missile sites, and protected the citizens of the USSR from the threat of nuclear strike from the West.

A large and boisterous tour group was tailing me through the gallery, and the English speaking guide appeared and suggested we head for the UCP before them, otherwise the wait for access to the Post could be considerable.

I followed the guide out of the gallery, across a short path and into another building, where we started our descent. The corridor was low and narrow and the concrete steps well worn. My guide explained that the corridor was intentionally small, and followed a gentle curve, so it could be defended by only two soldiers. The concrete surrounding the corridor was metres thick to protect access during an attack.

We emerged at a junction of corridors, and followed another to the elevator that would take us down 30 metres to the UCP. Electrical cables, insulated pipes and ducts ran the length of the corridor. Air had to be piped in to cool the mountain of electronics inside the UCP, plus the temperature and fresh air regulated inside the command room to accommodate the duty officers.

We reached the end of the corridor, where two enormous steel doors lead to the elevator. My guide told me that when operational, the door system was a little like an air seal on a submarine: it was only after one door had been opened, the two crew passed through, and the door closed behind them, that the next door could be opened. This was to minimise the number of people that could access the elevator at any one time, and protect the UCP against blast damage.

When we passed through the doors and entered the elevator, it became clear why the guide had suggested we head for the UCP before the tour group. There was just enough space for the two of us, and the only way to fit in my small backpack was to wedge it between my legs. This was once again by design: It only took two officers to command the UCP, so restricting further access minimised the chance of accident or effective attack. Apparently during busy tourist times the queue for the elevator stretches down the corridor, and visitors can be waiting for an hour or more to descend into the UCP.

When inside the lift, I was shown a tiny escape hatch in the roof, permitting emergency access to the elevator shaft. ‘You’d want to be small to fit through that’ I said. The guide replied ‘When there is an emergency in a place like this, you will make yourself small’. I reckon he’s right.

My guide closed the elevator door, pressed a button on the control panel, and we started to descend deep into the earth.

To be continued…

For the Museum’s website click here

If you liked this post, you may also like Museum of Strategic Missile Forces II, Visiting Chernobyl Part I

Do you have a particular interest in World War I, II and the Cold War? Check out my other blog Ghosts of War. If you enjoy military history, and want to know what it’s like to visit both significant and lesser-known wartime locations today, there’s something there for you.

Leave a Reply