Fear and fascination beneath the waters of Gallipoli

For most Australians, the Gallipoli campaign conjures images of soldiers fighting grim and desperate battles on the steep country above ANZAC Cove. However the struggle for control of the Straits of the Dardanelles began as a naval operation by the Allies, and it was only after this failed that a land invasion was attempted. Naval support, in firepower, supply and evacuation, continued throughout the 10 month campaign. Turkish shore batteries, mines, German submarines and accidents sunk more than 29 Allied vessels and killed over 1500 sailors. Included in the lost shipping were HMS Lundy and HMS Louis.

I had read that it was possible to dive on a few of the WW1 wrecks off the Gallipoli coast, and set off to make some enquiries when I reached Canakkale. I walked the cobbled roads from my apartment to where the only dive operator in town was supposed to be, and found no trace of it. I had passed a dive shop the day before, so found my way back there and asked if they knew of anyone that was running trips to the wrecks. They gave me a post-it note with a name and number to contact.

Back at the apartment I messaged the number, and received a reply from the bloke saying that he was not conducting wreck dives. It seemed like I was out of luck. Without much hope, I asked him if he knew of anyone that was running tours, and he gave me a name: ‘Mr Ali’. It sounded a little mysterious, but it was my last chance, so I messaged Mr Ali.

It turned out that Mr Ali was indeed running wreck dive trips, and although he was flat out, he could squeeze me on to the boat for the weekend’s diving. You beauty!

On a warm and sunny Saturday morning we headed out from the small port village of Kabatepe , then north to Suvla Bay. Our first dive was to be on HMS Lundy.

The Lundy was a 188 ton trawler built in Hull, Yorkshire, and launched in 1908. She was commandeered by the British Navy and armed for use as a patrol boat. On August 16, 1915, she collided with the SS Kalyan, a 9,118 ton converted liner, used for delivering troops and freight at Gallipoli. Considering the disparity in size between the two vessels, it is little wonder the impact sank the Lundy, and cost one sailor his life. Historian Gordon Smith described the incident thus:

‘(HMS Lundy was) alongside SS Kalyan, taking on ammunition. Anchorage came under fire and master of the Kalyan decided to move position, slowly, with Lundy still secured. As more shells landed, one of them nearby, Kalyan increased speed and turned slightly, Lundy failed to hear the shouted warnings, her stern was dragged under the stern of the larger ship, the hull holed by the propeller, and she flooded and sank…’1

Nearing the site where the Lundy lay in 28 metres of water, we pulled on our wetsuits and diving gear. The diver that secured the mooring line told us that visibility was poor initially but then cleared deeper near the wreck. After hearing this, and being a relative newcomer to diving, I was determined to stick close to the others during the descent.

In the choppy water, we bobbed around the mooring line, ready to follow it down to the Lundy. It was my first dive in a while, and whilst this probably wouldn’t worry a seasoned diver, I was a little anxious. The leader gave the signal, and down the rope we went, closely following each other one by one. At this point I have to admit that I found the dive a little scary. The poor visibility was caused by mucilage, a greeny-grey slime resulting from algal growth in warm, nutrient rich water. I had only ever dived in the crystal clear Red Sea, and the first metres down were like green pea soup. It’s interesting how being near-deprived of a sense whilst in an unnatural environment plays on the mind, and I was pretty nervous as we descended. A couple of small niggles with my gear didn’t help either. When we got under the mucelin layer things cleared up, and I was pleased to have a clear view of my dive buddy.

The Lundy came into sight, it’s rusting surfaces mottled with encrusted sea life. We made our way slowly from the bow to the stern, and I was amazed at how little the wreck seemed to have deteriorated in the 106 years she has lied on the sand. The damage caused by the impact with the Kalyan was clear, and included deep cuts in her stern.

The water temperature at 28 metres depth was cold, and before long I was shivering. Time seems to go faster underwater, and before long we were ascending the mooring line to our safety stop at 5 metres depth. I think we were all happy to see the end of the three minute pause in the ascent so we could surface, climb onto the heaving boat, and warm up.

After lunch and a relax on board we motored into a more sheltered spot closer to the coast within Suvla Bay.

‘Last night was very rough, and several lighters were wrecked on the beach. We also lost a destroyer which ran on the rocks just off West Beach. No loss of life.’ Major J. G. Gillam, Suvla Bay, November 1st, 19152

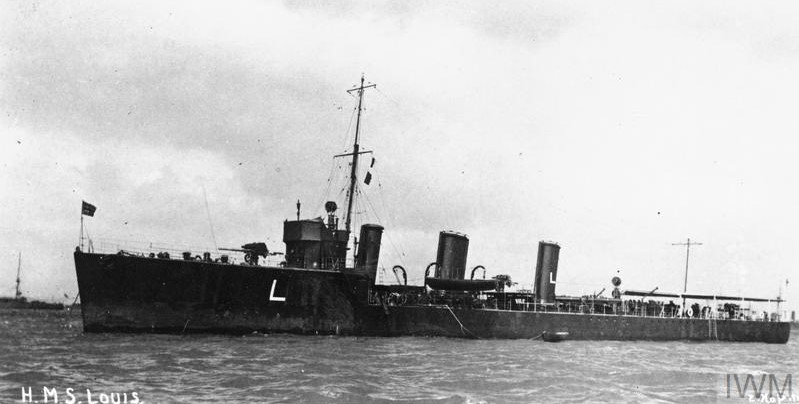

The destroyer to which Major Gillam referred in his diary was the 956 ton HMS Louis, thrown onto the rocks in the early hours of the morning during a gale in Suvla Bay on the 31st of October, 1915. The crew abandoned the ship and there was no loss of life. In the proceeding days, Gillam noted:

‘Destroyer which ran on the rocks yesterday still in the same position.’ November 2nd, 19152

‘Destroyer…is a total wreck, waves breaking over her.’ November 4th, 19152

‘The destroyer has now completely broken her back, and her stern has disappeared. The Turks discovered the mishap, but they could not see that she was a wreck, as she is bows on to the Turkish position. Thinking therefore that the was still intact, though stuck on the ground, they attempted to finish her off, and for three hours shelled her. They only recorded two hits however…’ November 5th, 19152

I was pleased that the site was a little calmer, and that the first diver down had reported better visibility, for our second dive of the day. After being a bit rattled by the first dive I was looking forward to something a little less challenging. HMS Louis is 14m down, and our team of five descended freely in the still water.

Due to the damage caused by her grounding and subsequent shelling, and the time that had passed since her sinking, only the bow of the Louis has been located. Much of the wreck is under the sand, however there was still plenty to explore.

My confidence returning, I relaxed into the dive and was able to focus on the wreck and the cool environs at the bottom of Suvla Bay. The most prominent feature was the row of steam boilers, clearly visible now the ship’s superstructure has gone.

Damage to the deck may well have been the result of the Turkish shelling whilst Louis sat helpless on the reef.

After spending time on the Louis, we surfaced, got changed and secured the gear for the trip back to Kabatepe. On the way we had a clear view of the coast from Anzac Cove (just to the right of the bare patch on the hills) up North Beach to Suvla Bay.

I was very glad I had been able to track down a dive operator on the peninsula, and managed to squeeze onto the packed boat for the day. It was fascinating to learn more about the maritime history of the Dardanelles conflict, and to have the chance to visit HMS Lundy and HMS Louis, two important historic sites lying beneath the waters of Gallipoli.

1Smith, G. (2016) ‘British Naval Vessels Lost, Damaged and Attacked by Name, 1914-15, some 1916-19’, BRITISH WARSHIPS and AUXILIARIES LOST, DAMAGED and ATTACKED by NAME (naval-history.net)

2Gillam, J.G. (1918) ‘Gallipoli Diary’, George Allen and Unwood, London

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like Visiting Gallipoli, Diving the S.S. Thistlegorm

Do you have a particular interest in World War I, II and the Cold War? Check out my other blog Ghosts of War. If you enjoy military history, and want to know what it’s like to visit both significant and lesser-known wartime locations today, there’s something there for you.

Leave a Reply